Ghostface: Do you like… [dramatic pause] scary movies?

Me: Could you be more specific?

The weird thing about scary movies—what a lot of people call scary movies—is how many of them aren’t all that scary. Slasher films thrill, body horror shocks, ghost stories disturb, torture porn (I really hate that term) repel. But scare—that is, trap you in that region between fight or flight, where you dread what you will see next, yet are incapable of looking away? Nah. Even the movie that coined the “Do you like scary movies?” bit, Wes Craven’s Scream (1996), isn’t a scary movie. It’s a comedy, Craven’s metacommentary on the slasher genre. There ain’t a frightening second in the entire runtime.

I will say this now: The Australian film, The Babadook (2014), scares the living shit out of me. Not just once, but every time I’ve seen it. (Yesterday was my third viewing.) Even better, it does it by deploying a variety of tools to express a viewpoint seldom encountered in the genre.

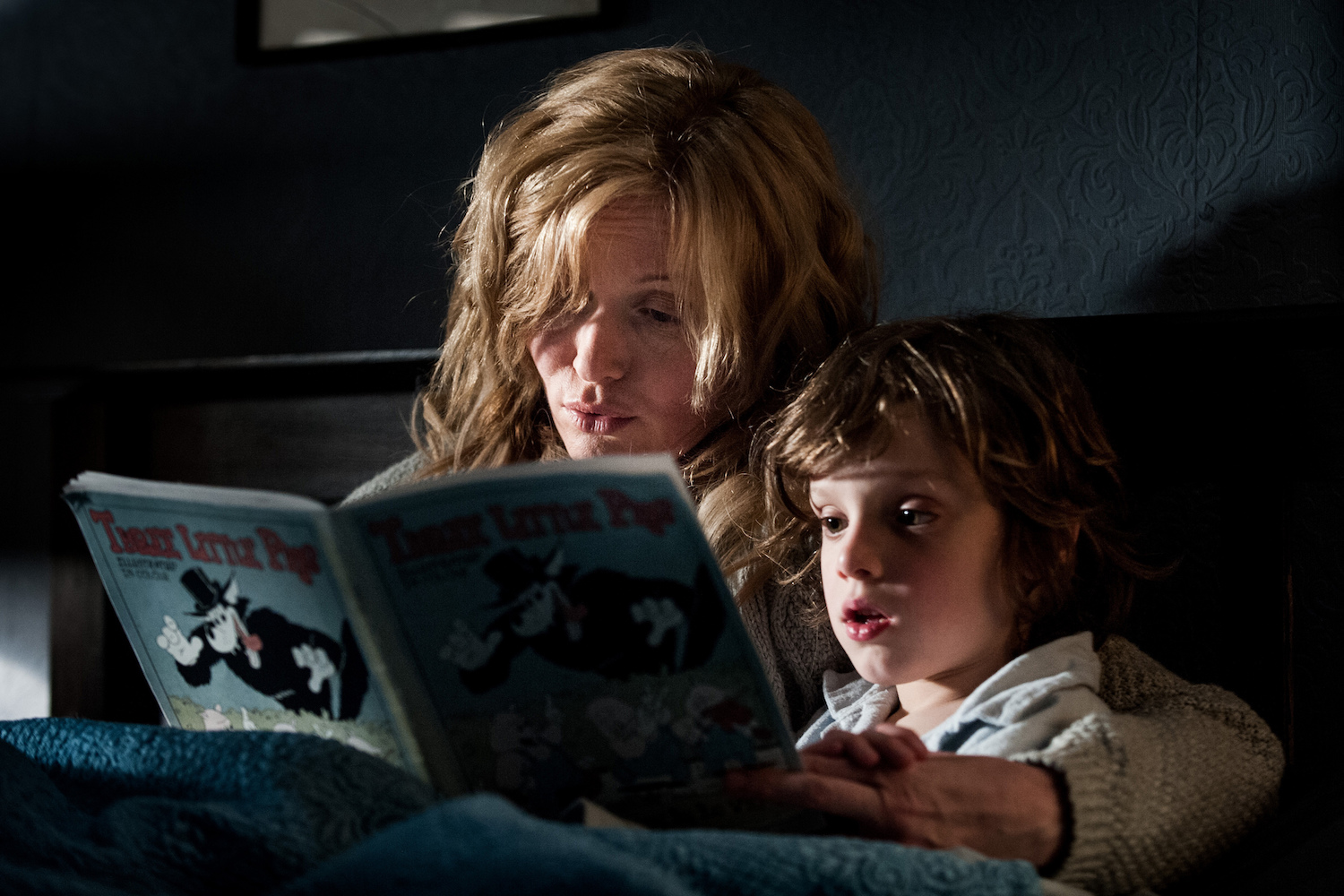

There really isn’t a comfortable moment in The Babadook. It starts with a stylized recreation of a living nightmare: A car accident in which the protagonist, Amelia (Essie Davis), loses her husband as he is driving her to the hospital to have her baby. Soon enough, we discover that what we’re seeing actually is a nightmare (writer/director Jennifer Kent gives us some sublime imagery when Amelia wakens, having her fall in slo-mo out of her agonized revery and into her bed), which is broken when Amelia is wakened by her son, the six-going-on-seven Sam (Noah Wiseman), who summons her to his room for what appears to be a nightly ritual of making sure his closet and the region under his bed are monster-free.

Young Sam is, to put it mildly, a handful. He’s fearful and clingy (in a disturbing moment, Amelia pushes the boy away when he hugs her too tightly). He is obsessed with protecting himself and his mother from monsters, and gets thrown out of school for bringing a makeshift portable catapult to class. He is impulsive in all the wrong ways, constantly pestering Amelia for her attention, injuring himself on the jungle gym during a demonstration of courage, alienating his classmates and the young cousin with whom he shares birthday parties (not because they have the same birth dates, by the way, but because Amelia cannot bear to commemorate the actual day he was born).

And that’s before the night that Sam pulls from his shelf a strange, rough-hewn pop-up book for his bedtime story. Mister Babadook starts off in Tim Burton cute-creepy mode, introducing a weird, top-hatted, not-quite-human entity that insinuates itself into a boy’s home. But the narrative soon turns ominous, and the then downright terrifying, as the specter grows, reveals rows of razor-sharp teeth, and is last seen rising up over the hapless boy that let him in.

And if Sam was a mess before, Mister Babadook sends him over the edge. He’s unable to fall asleep, swears he sees the Babadook everywhere, and traumatizes his peer group with warnings about the monster. Amelia attempts to exorcize the demon first by hiding the book, then ripping up the pages and tossing them in the trash.

To her surprise, the book turns up back on her doorstep, with the pages reassembled and new ones added indicating that the Babadook will soon track her down, invade her soul, and drive her first to filicide, and then to suicide. She starts to get phone calls in which a guttural voice utters, “Baba-dook-dook-dook,” and begins seeing the monster manifesting in old movies on the TV. (In an interesting nod to film history, Kent largely uses the public domain films of the father of special effects, Georges Méliès, while the Babadook itself is modeled on a character Lon Chaney Sr. developed for the now-lost silent horror film London After Midnight.)

And then, one night, something enters unbidden into Amelia’s bedroom. And enters, unbidden, into Amelia herself.

And to better explain what follows, and why it so terrifies, I have to make an odd but relevant digression. It used to be that when people were discussing the misanthropic comedy of W.C. Fields, it wasn’t uncommon for someone to note, “Oh yeah, in one of his films, he actually sends a blind guy into oncoming traffic.” That isn’t quite accurate—the sequence in question is not as bad as is typically summarized. It’s actually worse.

The film is It’s a Gift (1934). It’s pretty much a string of discrete set pieces, one of which has Fields, as the henpecked husband Harold Bissonette, trying to run his grocery store despite a string of small disasters and irritating customers, the most irritating and disastrous of which is one Mr. Muckle (Charles Sellon).

Mr. Muckle is blind and deaf. He is also, as a polite person might put it, a difficult man, or as Monty Python might put it, a right bastard. He’s foul-tempered, ornery, and careless, first putting his cane through the store’s front-door window, then upending cases of glassware and decimating a pyramid of unprotected lightbulbs. Bissonette is deferential to the old cuss despite the chaos he leaves in his wake (“SIT DOWN, MR. MUCKLE, PLEASE!”), all the way to arranging a delivery run for the single pack of gum Muckle has purchased, and then making sure the street is clear of traffic before sending the man back to his job (which, in a punchline that by the time it lands is really beside the point, is as house detective at the neighboring hotel). Once the dick (in all senses of the word) is on his way, and too late for Bissonette to come to the rescue, Muckle is immersed in an onslaught of speeding fire trucks. Through some miracle, he manages to make it across the street unmolested, while Bissonette collapses butt-first into a garbage can.

Here’s where people get that scene wrong: Bissonette does not deliberately send Muckle into oncoming traffic. And here’s where they get it right: W.C. Fields, who scripted most of his films, does. And he does it in a way that winds up brutally indicting the audience.

We, most of us, possess enough empathy to know to defer to people with disabilities (ask any disabled person and they’ll let you know that sometimes people overshoot the mark, but better that than the alternative). Fields presents us with a damning contradiction: A man who at once should instantly prompt our desire to assist (if needed), and yet who is such an unholy crud that we can’t help but wonder if we are—to use a favorite, Fieldsian term—being taken for suckers. By the time the oblivious Muckle makes it across the street unscathed, Fields has turned our sympathies so far around that we don’t feel relief that the man wasn’t reduced to a smear on the asphalt, but wonder at the irony of a universe that will go out of its way to spare the life of a truly unpleasant person. There’s a ton of hilarity in the sequence (while Fields is best known for his verbal gros mots, he could also deploy exquisitely timed physical comedy), but it turns out that the final joke of our encounter with Mr. Muckle is the one that’s on us.

As with our empathetic instincts toward people with disabilities and others who might be more vulnerable than ourselves, we are hard-coded to protect children. Amelia has struggled under that innate obligation for six years, compelled to sublimate her rage and guilt in order to concentrate on the daunting task of being a single mother. Sam, meanwhile, perhaps sensing the dark emotions roiling within Amelia, has become so obsessive about monsters—out of fear for his own safety and because he’s scared of the prospect that his guardian might be taken away—that he becomes a clinging, impulsive trial, one with whom even the most loving parent would have trouble coping.

When the Babadook enters Amelia, all the suppressive stops are thrown off. She becomes verbally abusive, stops tending to Sam’s needs, and for all practical purposes barricades the two of them in their home. Within the logic of the film, she is possessed by a monster. Take a step back, and she is recognizable as the worst-case scenario of an abusive parent, venting her anger at a vulnerable child, remorseful in the next moment, utterly irrational. At one moment in the film, when Sam cries, “You’re not my mother!” Amelia counters with, “I am your mother!” And they are both right, Sam seeing the monster that has taken control, Amelia, finally, revealing the part of her that blames, rightly or wrongly, this young creature for taking away the man she loved.

And here are the moves Kent executes that makes The Babadook so terrifying: She carefully establishes Sam as the ultimate in difficult children—needy, fearful, impossible to control. Amelia in the meantime has so sublimated her trauma—she bristles when anyone dares to even mention her husband’s name—that we can see how close she hovers to the breaking point. When she finally crosses the line, we realize that Kent has maneuvered the character dynamics to a place where we realize that now, anything could happen.

This is not a slasher film, where it’s guaranteed that the virgin will live past the credit crawl; this is not Saw, where victims are subjected to simple-minded, Irony 101-style punishments. The director has removed the safety of predictability, and emphasizes the danger by having Amelia perform a truly atrocious act (which I won’t elaborate on here) and having Sam reveal more and more of his vulnerable innocence as his mother becomes ever more unhinged. We are in unknown territory, a place where the awful prophecy contained within the pages of Mister Babadook becomes a too-present possibility.

[And we’ve also arrived at a point where in order to fully explain the hammer blow of The Babadook’s finale, I have to venture into spoiler territory. You’ve been warned.]

The film’s final act is a nightmare of physical and emotional violence. Amelia, driven mad by Babadook-invoked manifestations of her husband, becomes determined that she and Sam should join her dead spouse in the Great Beyond. Sam, having none of it, knocks his mother cold, and binds her to the floor.

But at the moment when we dread what will occur next, Kent pulls a switch: As Amelia rages, Sam tells her he loves her, tells her he knows it’s the Babadook in control, and urges her to find the will to exorcise it. Kent doesn’t simplify the moment—Sam, with the innocence of a child, caresses his mother’s face; Amelia, breaking free, comes close to throttling him. But in the heat of her mania and through the strength of her son’s unconditional love, Amelia manages to find her own love, succeeding in expelling the monster in a gout of black bile. From a first-person perspective, we watch as the Babadook flees, retreating to the house’s basement where, not so coincidentally, Amelia has sequestered all of her husband’s belongings.

The finale shows Amelia finally at peace, and happily prepping for Sam’s birthday party. But a task must be performed first: Bringing a dishful of worms—freshly dug from the garden—down to the thing that dwells in the basement.

It’s not unusual these days for a movie monster to survive past the end of a film. Can’t have sequels without it. But Kent has something more powerful in mind by letting the Babadook live. When the monster in the basement tries to attack Amelia, instead of fighting back, Amelia mollifies it, whispering, “It’s all right. It’s all right,” until the beast calms, and snatches the dish away into the darkness.

And this is the journey The Babadook takes us on: From subtle dread, to outright terror, to miraculous reconciliation. It tells us that there are some things dark, and unpleasant, and sometimes even monstrous that cannot be killed, that the best that can be done is be aware of their existence, try to understand why they are there, and learn to live in some kind of tentative harmony with them. The Babadook explores the horror of the worst aspects of the human soul, and somehow, surprisingly, imbues us with a sense of hope. It says that, even in the deepest depths of darkness, we can find our way to the light.

Is it okay to cry at the end of a horror film? The Babadook does that to me every time. I really hate the phrase “Instant Classic”—it’s a blatant contradiction in terms—but if any film deserves it, it’s this one, both for the skill with which Jennifer Kent orchestrates the terror, and for the way she offers a vision of the human condition from a perspective not often presented in the genre. Is this the only example? Probably not. Maybe there are other horror films that evoked true terror in you, or touched you in places you least expected. We’ve got a comments section below for just such thoughts; you’re free to post there. Be friendly and polite, though. Let’s all act through the lens of love.