It’s one of architecture’s painful paradoxes: Within academic institutions, the most engaged workers are often the least supported. How can precariously employed faculty convincingly guide students to stable careers? This contradiction undermines the very foundation of architecture education.

Recent motions to organize professional architecture workers into unions have drawn attention to the comparably tenuous conditions faced by architecture educators, namely adjunct faculty. Often juggling multiple jobs and institutions, adjuncts form the backbone of architectural education. They comprise the majority of architecture faculty—54 percent, according to the latest National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) annual report (2023). Adjuncts are known to bring innovative teaching approaches and on-the-ground experience to the classroom, yet they are systematically excluded from institutional decision-making, notoriously underpaid and overworked, and denied the research support, benefits, and security their full-time colleagues enjoy. What’s more, research has shown that the unrecognized burden of academic service, student mentorship, course preparation, and unpaid guest appearances falls disproportionately on untenured adjunct faculty—particularly women.

Recognizing this disparity, a group of adjunct faculty recently convened at The Architectural League’s offices to shed light on our own experiences of these conditions. Representatives from private institutions like Columbia/ Barnard, the Cooper Union, the New School/Parsons, Pratt, Syracuse, Cornell, and Yale, as well as public universities like CUNY and Kean, were in attendance. We, authors of this op-ed, were present. Our findings? Insufficiently addressed and inadequately documented, architecture adjunct precarity is a stark symptom of wider systemic issues. The precarious conditions of architecture workers straddle both the academic and professional realms, entangled in a web of challenges that interact, converge, and amplify one another. Our tacit goal? To sketch a blueprint for structural change and equity in architecture education. Organizing will constitute its binding force.

The Organizer’s Guide to Architecture Education

At its core, organizing is the practice of building collective power to address shared predicaments, catalyze transformations that benefit the majority, and pursue coalescing goals unattainable by individuals alone. The recently published book The Organizer’s Guide to Architecture Education (TOGAE)—coauthored by one of us—posits that organizing is crucial to overcoming the compounding crises exemplified by adjunct worker precarity. It employs a versatile, scalar framework applicable by organizers across various fields and positions, including adjuncts.

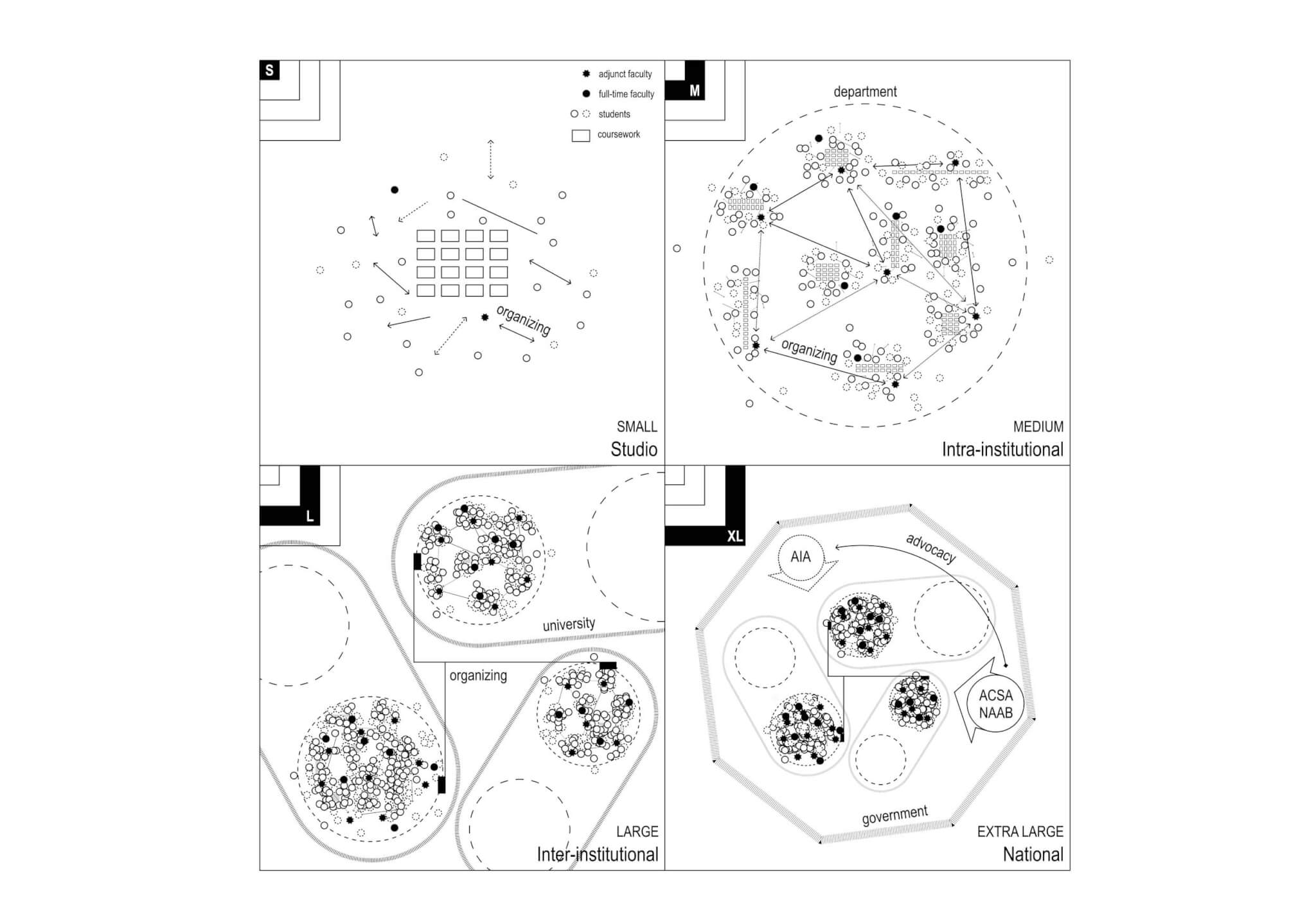

Informed by the intersectional challenges faced by marginalized groups such as adjuncts, TOGAE’s configuration offers to drive systemic change through a heuristic process—a practical, hands-on approach based on experimentation and discovery. It leverages a scalar lens to address the complex predicaments in architecture education. This instrumentation enables organizers to identify intervention opportunities at different scales, fostering coordinated strategies that build diverse yet cohesive grassroots power. Linking these actions allows efforts to reinforce, mutualize, and expand each other, ultimately driving broad systemic change.

S, M, L, XL

TOGAE breaks down architecture education into intelligible parts: SMALL, the studio; MEDIUM, the curriculum; LARGE, the university; and EXTRA LARGE, the nation-state. TOGAE coauthors explain this choice was inspired by Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau’s tome of the same name: “the language of S, M, L, and XL defines an organizing framework for mapping the specificity and interconnectedness of both existing conditions that define architecture education and strategies that can mobilize it toward systemic change.”

The recent adjunct strike at the New School (TNS) is an example of a coordinated, scale-specific action. In November 2022, TNS members organized a record-breaking 25-day strike involving 1,678 adjunct professors, comprising 87 percent of the faculty. The strike’s origins lay in the microcosm of TNS classrooms (SMALL), where the university’s progressive legacy nurtured innovative pedagogies. This seed sprouted when conversations between adjuncts from different departments gained momentum (MEDIUM)—and students eventually took to the streets in solidarity with their professors. These departmental discussions grew the strike to its full magnitude, encompassing the entire university (LARGE), with the ACT-UAW Local 7902 union negotiating with TNS administration. The broad movement was thus built upon the foundation of smaller, discipline-specific coalitions.

However, while these achievements were substantial for TNS, they did not address the systemic issues facing adjuncts across higher education (EXTRA LARGE). The persistence of these broader challenges underscores the need for a more comprehensive, interinstitutional approach and for reexamining the dynamics of the profession and its jurisdictions at the nation-state scale.

TOGAE’s scalar framework illuminates how to build effective coalitions spanning multiple structural dimensions. Our approach links scale-specific actions, from studio to curriculum and university to nation-state, and enables organizers to leverage coalition-building for more significant impact.

Scales of Action

At the SMALL scale (the studio), the architectural worker is shaped and the potential for change begins. By reimagining studio culture, as adjunct instructors are keen to do, the studio becomes a space for cultivating architect-citizens who are responsible for and to each other. This approach emphasizes cooperation, challenges traditional power dynamics, and fosters empathy and mutualism across positions of power. Students are empowered to take control of their pedagogical experience and develop their agency as political subjects when learning to organize and support one another.

At the MEDIUM scale, organizing within architecture schools reimagines curriculum as a laboratory for practice, where improved conditions for adjunct faculty are integral to developing better models of doing and laboring within architecture. This holistic approach integrates curriculum development with reimagined departmental processes, advocating for enhanced teaching and research opportunities, career development, livable wages, benefits, and job security. Architecture education becomes a space to test, challenge, and innovate new modes of working and relating, addressing immediate needs while laying groundwork for broader institutional change that spans both MEDIUM (school) and LARGE (university) scales.

This intraschool momentum directly extends to interschool collaborations. School-specific groups connect with counterparts at other universities, building collective power to influence national organizations. During The Architectural League’s roundtable, participants suggested that the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) and NAAB collect more detailed data on adjunct labor conditions in annual reporting. AIA could provide support by raising consciousness about labor issues. These initiatives bridge the MEDIUM (departmental) and EXTRA LARGE (national) scales, catalyzing comprehensive paradigm shifts in architectural education.

At the LARGE scale, where university budgets and faculty salaries are determined, architecture-specific groups can expand their reach by collaborating across departments to build solidarity with staff, administrators, and students. This cross-disciplinary approach strengthens the overall adjunct movement and targets the institutional level, where substantive change in adjunct conditions is possible. The overlapping networks—inter-architecture-school and intra-university-inter-department—must coordinate to create a robust organizing culture that can effectively advocate for budget reforms and fair compensation.

At the EXTRA LARGE scale, these networks collaborate to address systemic issues at the nation-state policy level and aim for an epistemological and ontological shift necessary for meaningful long-term change. Drawing from campaigns like the Debt Collective’s student debt relief, adjunct organizers could join forces with university administrators to advocate for increased federal funding, recognizing that improving adjunct conditions strengthens universities overall. This multipronged approach—combining policy advocacy, institutional reform, and the reimagining of fundamental concepts—seeks to enact structural changes benefiting educators and institutions alike. Change comes from multiple directions: Individual universities serve as innovative models, while broader societal pressure influences widespread approaches. This combination is crucial for realizing a just and sustainable future for architecture education and practice.

Breaking Ground

To turn our vision into fruition, adjunct organizers invite participation from readers. We urge all architecture adjunct educators to complete a comprehensive, anonymous survey for each teaching position that they have held. Your input is crucial in building a solid foundation for advocacy. The survey (QR code below) aims to capture a range of experiences and paint a detailed picture of the adjunct experience across regional and institutional contexts.

Looking ahead, efforts will focus on building momentum through interinstitutional, adjunct-led campaigns, bolstered by national organizations such as ACSA and AIA. These strategic partnerships and collaborative efforts can amplify the movement’s impact and reach. We invite these organizations to join us in addressing these issues through advocacy and action. Educators teach the necessary skills and knowledge that equip future practitioners and offer access to a historically exclusionary profession. Students discover creative approaches and innovative methodologies through their exposure to diverse ways of thinking about architecture. Adjuncts benefit from the experimentation allowed within the university sanctum—where the pursuit of knowledge, critical thinking, inquiry, and debate are traditionally protected—as a complement to the more risk-averse realities of architectural practice. As a discipline, we’re responsible for dismantling the vicious cycle of insecurity that constrains our community.

This road map provides a comprehensive approach to addressing challenges faced by architecture adjuncts. Collaborating across multiple scales, the movement can work toward a future where adjunct labor in architecture education is valued and supported. The plight of the adjunct is a symptom of broader structural inequities and part of reshaping architecture education to address deeply systemic challenges such as climate change, social injustice, and unsustainable development. Moving toward a more inclusive architectural pedagogy requires looking beyond traditional academic configurations. This transformation embraces an “expanded, decentered field,” recognizing architecture’s interconnectedness with broader societal and environmental concerns. Addressing adjunct working conditions is a crucial step toward an educational environment that prepares students to tackle global challenges collaboratively. This shift positions architecture as a vital contributor to planetary stewardship, educating architects capable of shaping a more equitable, sustainable, and resilient future.

Lindsay Harkema is an adjunct educator and founder and cofounding member of WIP Collaborative.

Valérie Lechêne, TOGAE coauthor, is an architect and systems thinker advancing urban climate adaptation.