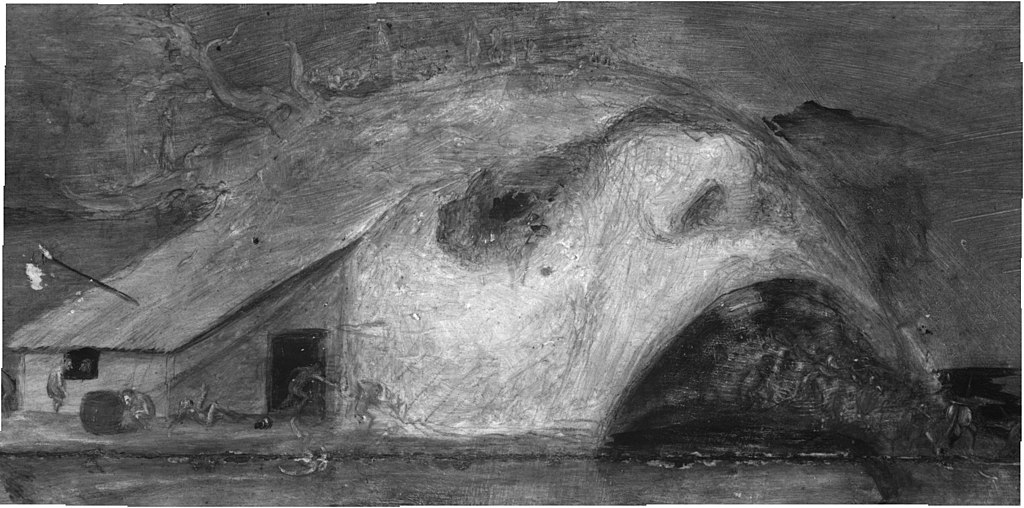

Infrared reflectogram detail of Christ’s Descent into Hell, a painting by a follower of Hieronymus Bosch, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC0 1.0.

It’s the tail end of January, the month of resolutions made and broken, gym memberships purchased and fitness classes left unattended. This week, we’re publishing a series of dispatches from the gym.

As a teen, the distance between the present and future was mysterious and unbreachable. Parental appeals to the future didn’t work. “Think of the future,” they said. But I couldn’t. I could picture a red bird. I could picture a lampstand. But the future? It was a phenomenological impossibility. Once the prefrontal cortex and temporoparietal junction in the brain have developed, it’s easier to imagine the mental states of others, or to imagine what your perspective, as a fictional Other, might be like one day. But in young teens, this capacity is still developing, so the future is a rush of action and anxiety—the future is the present moment—always unfolding as it’s being lived out, experienced in hazy and semi-articulate ways. When you are thirteen, you are not thirty-two. But when you’re thirty-two, you’re also not thirteen. And this is similarly hard to understand.

It’s hard to understand because it’s not something you typically think about. You never think, I’m not thirteen!

But then one day I thought it. I understood it. I understood it in the vibrating around my eyes; in the way my shoulders retracted against my spine. I was twenty-seven at the time. I had known that I was twenty-seven—I had celebrated my twenty-seventh birthday just one month prior, for example—and I had known that I was getting older, but I had not known about the terrifying, gurgling stuff of time that would soon enter me.

I was visiting Ohio, where I grew up, over the holidays. I’d been living in Maryland. Some of my friends and my brother invited me to play basketball at the local recreation center. The Solon rec center had a small climbing wall in the center; the locker room behind it smelled like chlorine, which leaked out across the lobby. When we arrived, I felt a chilly premonition. The basketball court shrank into a point in the distance, and my perspective seemed to detach and then zoom out, like a traffic camera. It was swarming with kids who appeared to be thirteen.

“Let’s leave,” I said. “The court’s full.”

“We can just wait,” my friend Ziggy said. He was, I noticed with horror, visibly twenty-seven.

Among the squeaking sneakers and balls, I felt time crumple into me. I felt the rush of years behind my cheeks. As a teenager, I knew about teenagers and I knew about grown-ups. But I didn’t know about the space between, the period of technically being an adult but not having any of the markers of adulthood: normal career, kids, and, most importantly, a place to be on a weekday afternoon, any place to be, other than the basketball court at the rec center in the town where I grew up.

“It’s fine,” my brother said, “let’s take one of the side hoops and just shoot around.”

We put our belongings on the floor, against the wall, and started shooting. I felt self-conscious. As far as writing novels went, I was young—literature was generally a second-half-of-life game. But many of the most famous NBA players were my age or younger. Every time I missed a shot, I felt the impassable stretch of years between us and the teens. I felt the heat of many made-up eyes. On the court at the rec center, it was fine to be young, and it was fine to be old. But it was not fine to be twenty-seven.

I asked again if we could leave.

Then, I heard a voice.

The voice came from behind me. I couldn’t place it. Ziggy? My brother? The voice called out again.

“Fours?”

A teenage boy was gesturing with his hand at three more teens, all standing and staring expectantly.

“Fours?”

I stood frozen. I wished that I had shaved. I remembered Goober, an alcoholic, mentally disabled, semi-mythical figure who would wander around my town when I was in middle school, and was rumored to have been hit by a car in his youth. I felt like Goober.

“Yeah,” my brother said, before I knew what was happening. “Let’s do it.”

I took my position at the top of the key. A lanky boy, who couldn’t have been older than fourteen, approached. He looked me up and down slowly—then looked away. “I got this guy,” he shouted to his friends. He was tall, and wore a smug expression that disintegrated me.

The game began.

We scored; they scored; we scored; they scored.

I shot and missed. My friend Evan shot and missed. My friend Zach shot and missed. But the teens kept scoring. Their bodies twisted balletically around me and my friends—who lurched like dry leaves, whose bodies were creakier, less fluid.

“Hell yeah, fuck them up,” one of the boys congratulated his teammate. “They got nothin’.”

I could feel my ears, which were attached to my head. But how were they attached to my head? Were my ears … weird? They felt warm.

“Guy’s a chump,” one teen said when Ziggy passed me the ball. “He’s gonna try and shoot a three.”

I tried to shoot a three. I missed.

The teens high-fived. They appeared menacing. They were kids. But they weren’t kids. Just like I was an adult, but I wasn’t an adult.

“Give it to me,” the teen I was guarding said. “He can’t guard me.” He looked at me. “You can’t guard shit.”

I couldn’t guard shit, but I also couldn’t talk shit because of the age difference. I imagined responding in kind and getting pulled aside by one of their parents. I imagined saying something too aggressive and accidentally breaking the imaginative play-space of the game, making it real. Trying hard to win felt inappropriate—they were kids—but taking it easy felt wrong too. The teenagers’ bodies were lithe and more capable than mine, their minds more elastically confident; there was a violence underneath their movements that I simply couldn’t contend with. They could kick my ass, I thought, horrified.

We lost. Then we played again and lost again. I thought of Shakespeare:

Youth is full of sport, age’s breath is short;

Youth is nimble, age is lame;

Youth is hot and bold, age is weak and cold;

Youth is wild, and age is tame.

But it wasn’t youth that I encountered on the court. My first thought, upon later reflection, was that age jumped around in faces and made you think of your ears. That age bounced back and forth between the voices of young shit-talking boys, then shot your own voice down into the back of your throat when you wanted to talk shit in return. But I was wrong. It wasn’t age, or time, but eternity that confronted me on the basketball court. In situations that dislocate you, that defamiliarize your experience of time so that its true nature is revealed, eternity can manifest in subjective experience. When you’re a thirteen-year-old talking shit to a twenty-seven-year-old, despite your inability to really imagine it, time is linear. But when you’re a twenty-seven-year-old getting beat by a shit-talking thirteen-year-old, you are stuck in eternity.

“There are decades where nothing happens and there are weeks when decades happen,” Vladimir Lenin is alleged to have said. But Lenin never played basketball with young teens. If he had, he would have added: There are moments when decades and weeks melt away, and all that remains is eternity.

And this is the truth about eternity: There is no eternal chronological time, but there is a kind of dark eternity hidden in the faces of shit-talking teen boys. The teen boys were not an image of youth but a horrifying portal to hell.

***

I didn’t encounter any more teens until two years later, when I moved to Westchester County. My wife and I lived in a small cottage at the back of a rich widow’s property, butting up directly against hundreds of acres of woods. It was eerily idyllic, like the setting of a horror movie. The area was wealthy in a looming way I couldn’t comprehend. There was a law, an Uber driver told me, that no weight-lifting gyms were allowed in Mount Kisco—only “health clubs.”

Compared to Powerhouse Gym in New Haven, where I went for two years and where more than half of the guys were thirty-plus and on steroids and the speakers blasted Eminem and System of a Down, my gym in Mount Kisco—Saw Mill Club East—felt geriatric. Bright, tinny pop music played quietly from the speakers. There were massage tables out in the open on the gym floor. Elderly people walked around with medicine balls. But there were also teens.

The gym had a sauna. Many have extolled the benefits of the sauna in recent years. Lifespan, cardiovascular health, cellular regeneration, etc. But one underdiscussed aspect of the sauna is its strange, semi-anonymous intimacy. Near nakedness, dark wood, close quarters, heat. The sauna is a space outside time where heat causes you to be radically present.

It was the sauna in Saw Mill Club East that put me in proximity to Mount Kisco’s teens. Unlike the basketball court, the sauna allowed me to play a more comfortable role, one that didn’t force me to directly interact, or strike the paralyzing sensation of subjective eternity into my consciousness: The sauna allowed me to disappear into the heat and pay attention, like an invisible narrator. I was there but not there. I could watch and not participate—a disembodied consciousness suspended in heat.

On the afternoon of New Year’s Eve, I sat alone with three white teenage boys as they discussed their plans for the night. The sauna was small and we all sat on the top row. One of their shoulders was nearly touching my shoulder. Sometimes they did touch. When they did, I inevitably glanced over and shifted a bit. His skin was somehow both pimplier and smoother than mine.

“Come scoop me when my parents go to sleep,” the blond one said. “They go to bed early.” The blond’s voice squeaked like a sneaker.

“Then Becky’s?” another asked.

“Yeah. I’m going to take half an addy and some of that edible before I come out … Or maybe the full …”

“Don’t get too fucked up, bro”—laughter—“you need to make it up to Becky after last time.”

“Brooo,” the blond said, voice cracking, “I was—fff—man, come on, I know, I know, gahah.”

I focused my eyes on the brown wall in front of me; my skin tingled from heat. I felt aware of my tattoos, and though I was strong, I was also aware of my smallness relative to them.

“I got unresistible rizz,” the blond said, perking up. They were learning how to communicate with each other in front of me: Take the jokes; respond with bravado; maybe put someone else down. “You know how it is. Ahaaa.”

“Don’t tweak off the addy,” one of them warned the blond. “I remember last time you were tweaking.” He made a strange guttural noise, then paused. “And I think Sarah and Jessica are going to be there. So that should be interesting.”

“Did you hook up with Sarah at Jason’s?”

“Bro”—laughter.

I felt cozy, like my whole body had been dropped into noise-canceling headphones. But the white noise was in my body. The teens continued to discuss the most important parts of adolescence—doing drugs, lying to one’s parents, having sex—and I intuitively felt a deep sympathy with them. When the cruel light of winter morning descended on January first, I thought, they would feel lonely.

In the sauna, there was no dark eternity. Just the present in the heat, and a new year the next day.

***

A few months ago, we moved back to Maryland for a job I got in D.C., back into a house we had already lived in years prior. Time was swimming backward and forward and I wasn’t sure what it all meant. I couldn’t feel time in any meaningful sense. Even when I entered the house I used to live in, I didn’t feel a rush of memory. I experienced time in the present, but my memory of the house—like all memory—was static: It was impossible to relive lost duration, or to remember time. The familiar surroundings had a numbing, mildly comforting effect. I went and got a membership at Gold’s Gym.

In the sauna at Gold’s, which was a combination of Powerhouse and Saw Mill Club East—a real gym, but bright and silvery, a little too clean—college students talked about school, girls, lifting; jacked Ethiopian immigrants who became police officers disparaged the behavior of other African immigrant groups; elderly men lay down with towels on their faces; white middle-aged men listened to rap music loudly on headphones. My friend Pat came to visit, and after work one day we lifted and then went into the sauna. As we opened the door, an Asian teen, about fifteen, with long hair, was in the middle of saying “—kill myself, man. I was suicidal. I couldn’t see a way out.”

We sat down next to the Asian teen.

“Man,” a Black teen said. He was the only other person in the sauna, sitting on the far wall, on the lower bench. “I feel you.” A pause.

“I was heartbroken,” the Asian teen said. He adjusted his position on the bench. The teens were sitting far apart; they didn’t seem to know each other.

I exchanged glances with Pat.

“I’m good now, though,” he said. “Ever since I found Jesus.” He shook his head, and his hair, slick with sweat, glistened. “I wanted to die, bro. I literally had no reason to live. I didn’t want to. But then a family friend invited me to church and Jesus spoke to me. It was crazy, bro. I started crying. When they called for people to come up to the front to accept Jesus, I don’t know what happened. I just got up and I went. Jesus saved my life.”

Like the teens at Saw Mill Club East, his voice cracked when he spoke. However, he spoke with a kind of confidence that those teens didn’t have. His eyes had a brightness I associated with the Christians who scared me when I used to go to Protestant churches. His eyes cut through the dark sauna.

Pat and I looked at each other.

“I tried to kill myself too,” the Black kid said, looking down. “Three times.” The heat had started forming beads on my skin. “And after the third time, God saved me too. Shit.” He used a rolled-up shirt to wipe his face, then sat back against the wall. “I was living wrong. On drugs, doing all kinds of shit. I was raised Catholic, my mom was Catholic, but I never fucked with that shit. I was like, This is weird, bro, you know?” He laughed. “But I relate.” He paused. This was not like any other conversation I’d heard in gym saunas. I tried to think of what it was like, but I couldn’t. I had never experienced it before. I had had a dark year—death, mistakes, my in-laws’ house consumed by fire—and moved back to an old place for a new job. I had been to this sauna many times, but the strangeness of the conversation illuminated it: Had the sauna somehow gotten wider? Were the cracks in the wood floor new, or was I noticing them now for the first time? Augustine said there were three times: “the present of things past, the present of things present, and the present of things future.” But there was also a fourth time, one in which all three were present at once. On the basketball court, when a sliver of time was raised up out of the demoralizing parade of chronology, out of the voices of fourteen-year-old shit-talking boys and jammed into my head—puncturing the trudge of minutes, suspended there in panic—this dark kind of fourth time paralyzed me in unfamiliar fear. There was another kind of fourth time—the heavenly kind—but it was harder for me to understand. I sought it out, and the teens here tried to talk about it, but it was impossible to talk about—language easily killed it—so I oscillated between feeling awed and suspicious. Occasionally, I could feel this fourth time just outside of my sensorial ability, like I needed to develop a new sense organ in order to glimpse it, this other-dimensional reality that was always there, if only I could break through and encounter it fully. Chronological time degraded perception through habit. Language degraded perception through abstract categorization. But on the basketball court with the teens, I had no language or preconceived set of symbols to organize my experience and so was touched by a terrifying time-suspension—an encounter immune from the numbing effects of habit and symbol—pure, self-centered, throttling fear. Here, in the Gold’s sauna, the teens talked about their suicide attempts—their attempts to escape the misery of moment-to-moment succession in favor of some far unknown—but they had both encountered something else instead, which seemed to reach into their lives from beyond time to alter their experience of time, so that now they wanted more of it.

“God is good, man. Really …”

I looked at his eyes. They glowed too.

The teens went back and forth, and Pat and I stayed silent, sometimes nodding.

Then all at once the Asian kid sprung up. “I gotta go,” he said. “Time to get out of here.”

He made a peace sign with his hand and left.

A few weeks later, I encountered one of them again in the sauna, telling an even younger pudgy preteen that he had to keep a “roster” of women, so that “if your main acts up, you can threaten to replace her”—he was imitating the tone of certain podcast clips I’d heard—and that the point of life was trying to get money, to get jacked, and to get girls. Sitting next to him in the sauna this time, I discerned no touch of what had been present in the sauna weeks prior, only the world of accumulation in chronological time—the dry heat of the sauna pressing in—whatever outside-of-time experience that had been the subject of the prior conversation, which I’d felt moved by in the subsequent weeks, having withdrawn itself or been rejected in favor of the inevitably decaying stuff of this world.

Jordan Castro is the author of the novels Muscle Man, forthcoming from Catapult this September, and The Novelist. He is the editor in chief of Cluny Journal and is on the board of the DiTrapano Foundation of Literature and the Arts.