Atlas of Never Built Architecture | Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin | Phaidon | $150

In our dreams, the world is much more vivid than what we experience when we are awake. The same is true of architecture: What we imagine, either as designers or as users, is more vivid than what is built. That is because in our imagination there is no gravity or any other constraint on form. Buildings can reach to the skies, have as many colors as the rainbow, and merge with nature without seams. There are no budgets, regulations, clients, or contractors to constrain us. Now we have a book to remind us what some architects have dreamed up: Atlas of Never Built Architecture, a hefty volume in which critics Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin have collected over 300 projects from around the world envisioned, but never realized, by architects of the 20th and 21st centuries.

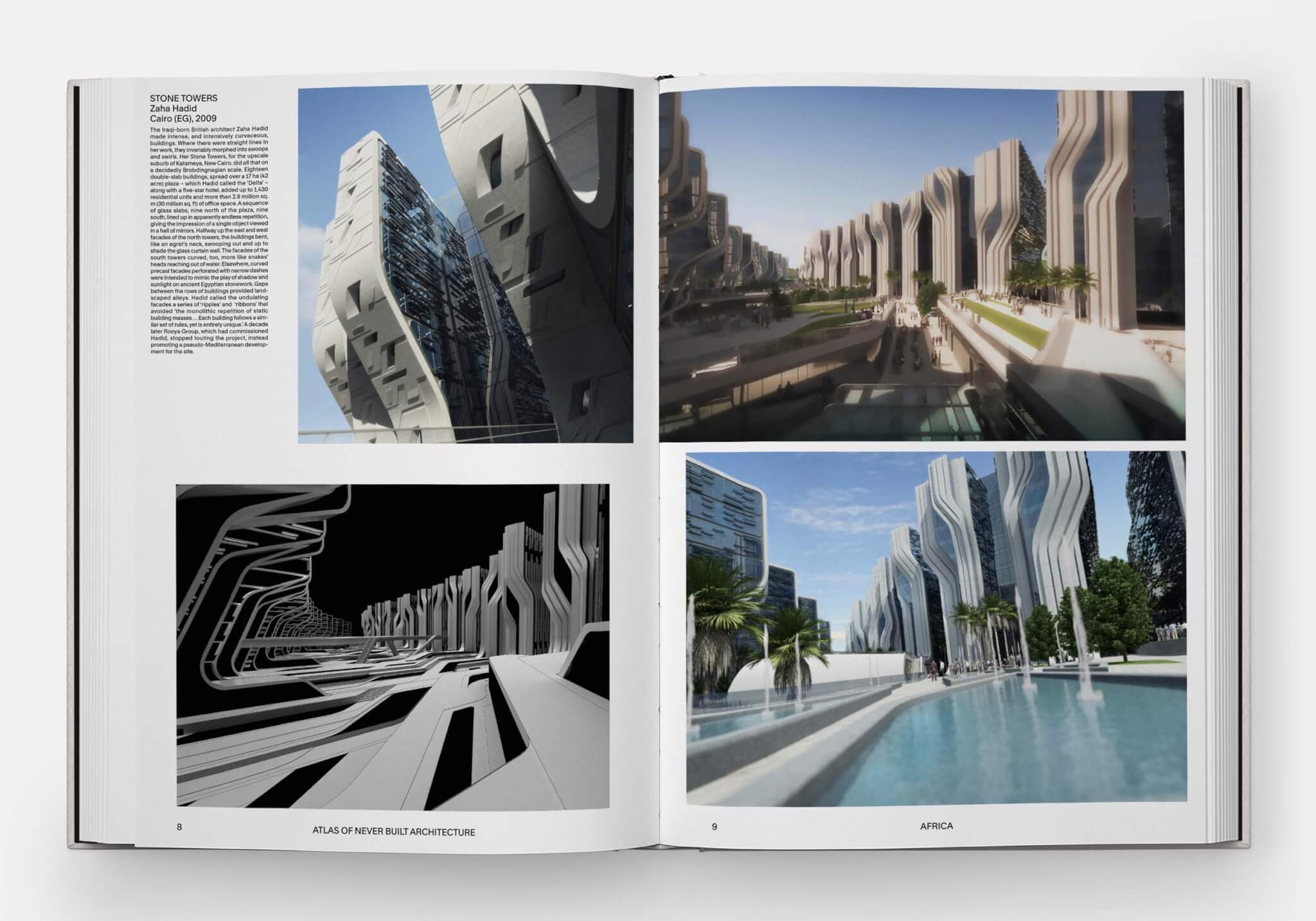

In truth, the book is not the “comprehensive global survey” the publisher claims it is, nor could any such a coffee table book live up to that ambition. Rather, its title should be Never Built Brutalist Architecture or, perhaps, The Unbuilt Big Buildings Book: Most of the work Lubell and Goldin have collected tends toward a Brutalist style and an imposing scale, a set of characteristics that makes the volume both more coherent and more restricted than its title implies. While its scope is truly global, with the volume divided up into chapters that cover every continent (with Europe being cut into a Western and Eastern section), the range of projects presented is rather narrower. Most of them are large object buildings, singular in their massing, expressive either in their form or in the manner in which the architect chose to render them (often from the position of a bug staring up at a looming edifice).

Lubell and Goldin do not confess to their bias, only saying that they eliminated some projects “because it didn’t fit into the category of architecture,” without ever defining what that means except that it is not the “earth mounds” the artist Robert Smithson imagined for Dallas Fort Worth International Airport. What they do say is that what they have collected are “pure unadulterated visions” produced by “hero” architects. The implication is that more complex proposals—ones that are ephemeral or that were created by teams rather than (almost all male) utopians fell away in the editing process.

Their core achievement, beyond bringing together so many beautiful drawings and (pictures of) models, is to give space to “remarkable architects who were doing remarkable work beyond the canon,” such as Eladio Dieste, Geoffrey Bawa, and Hassan Fathy. Most of these architects are now part of the canon, at least in the schools where I have taught recently, but their inclusion thus represents the fact that our list of great buildings and architects has expanded perhaps even more quickly than the authors believe.

The focus gives us a parade of monuments that leaves other forms of architecture in the dust. We have quite a few projects by Coop Himmelb(l)au and others making expressive form, but none by SANAA or Lebbeus Woods; there are plenty of concrete bunkers representing postwar optimism, but nothing from Archigram, Archizoom, Constant, or any of the other architects who tried to bring the complexities and contradictions of popular culture into architecture. The preference for the monumental overrides the influential: For example, MVRDV gets three large Asian projects, while none of its arguably more radical and influential digital projects, such as KM3 or Costa Iberica, are represented. James Stirling’s megalomaniacal project for the Siemens headquarters outside of Berlin is here, but not his much more subtle and, again, vastly more influential designs for art museums in Cologne and Düsseldorf. On the other side of the urban scale, Le Corbusier contributes a few objects, but not his vision for the Plan Voisin wiping out Paris. Marion Mahony Griffin’s rather strange and, in my mind, forgettable King George V Memorial takes the place of her layered urban plans that were only partially realized in Canberra.

What is included overall is more than worthwhile. As is inevitable in such a compendium, there are a few rather mediocre projects that seem to here mainly to fill in geographic gaps, but there are more than enough visions, both well-known and obscure, that are so evocative as to make the book an enjoyable and inspiring read. I just wish Lubell and Goldin had made it clear what they believe in and why they thought projects worth including.

Certainly part of the decision-making process was the question of what would sell to the wider Phaidon audience. With a no more than serviceable design by the otherwise extremely accomplished Joost Grootens, the product is a nice-looking picture book of buildings, no more and no less. I just think that a few zap-pow images from the 1960s or some of the tactical urbanism projects created by collectives in the last ten years would have looked good in here. They would have helped construct an argument for architecture that imagines a better world, not just monuments towering over us. Images, forms, and even processes weave their way through our communities. Hopefully this fluidity will define the future of architecture—both built and imagined—rather than the ghosts of architecture’s past insistence on landing on us with a heavy thud.

Aaron Betsky is a critic of architecture, art, and design living in Philadelphia.