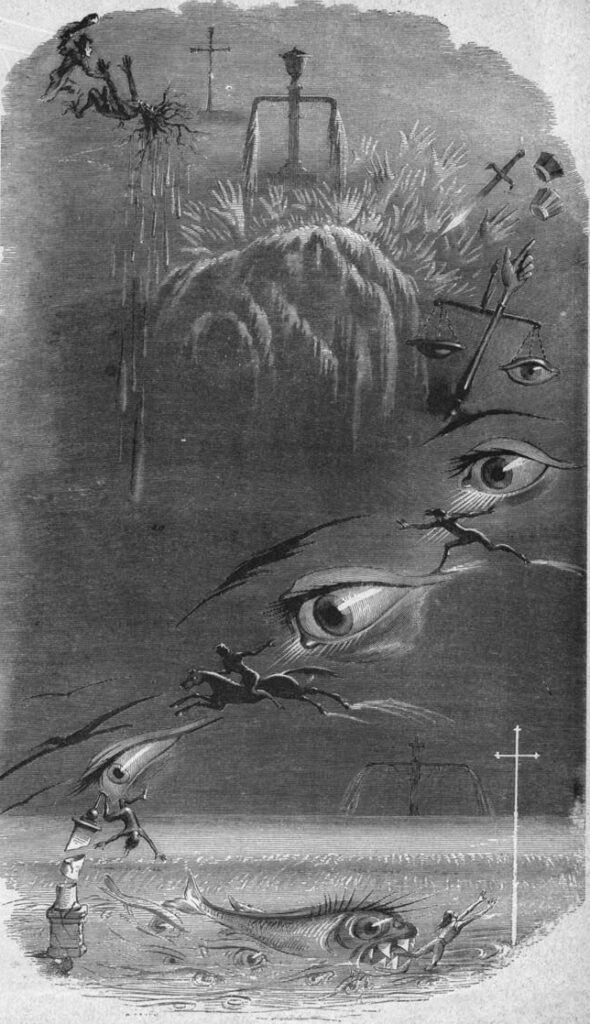

J. J. Grandville, A Dream of Crime and Punishment, 1847, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Charlotte Beradt began having strange dreams after Hitler took power in Germany in 1933. She was a Jewish journalist based in Berlin and, while banned from working, she began asking people about their dreams. After fleeing the country in 1939 and eventually settling in New York, she published some of these dreams in a book in 1966. Below, in a new translation from Damion Searls, are some of the dreams that she recorded.

Three days after Hitler seized power, Mr. S., about sixty years old, the owner of a midsize factory, had a dream in which no one touched him physically and yet he was broken. This short dream depicted the nature and effects of totalitarian domination as numerous studies by political scientists, sociologists, and doctors would later define them, and did so more subtly and precisely than Mr. S. would ever have been able to do while awake. This was his dream:

Goebbels came to my factory. He had all the employees line up in two rows, left and right, and I had to stand between the rows and give a Nazi salute. It took me half an hour to get my arm raised, millimeter by millimeter. Goebbels watched my efforts like a play, without any sign of appreciation or displeasure, but when I finally had my arm up, he spoke five words: “I don’t want your salute.” Then he turned around and walked to the door. So there I was in my own factory, among my own people, pilloried with my arm raised. The only way I was physically able to keep standing there was by fixing my eyes on his clubfoot as he limped out. I stood like that until I woke up.

Mr. S. was a self-confident, honest, and upright man, almost a little dictatorial. His factory had been the most important thing to him throughout his long life. As a Social Democrat, he had employed many of his old Party comrades over the past twenty years. It is fair to say that what happened to him in his dream was a kind of psychological torture, as I spontaneously called it when he told me his dream in 1933, a few weeks after he’d had it. Now, though, in hindsight, we can also find in the dream—expressed in images of uncanny, sleepwalker-ish clarity—themes of alienation, uprooting, isolation, loss of identity, a radical break in the continuity of one’s life: concepts that have been widely popularized, and, at the same time, widely mythologized. This man had to dishonor and debase himself in the factory that was practically his whole sense of self, and do so in front of employees representing his lifelong political views—the very people over whom he is a paternalistic authority figure, with this sense of authority being the most powerful component of who he feels he is as a person. Such humiliation ripped the roots up out of the soil he had made his own, robbed him of his identity, and completely disoriented him; he felt alienated not only from the realities of his life but from his own character, which no longer felt authentic to him.

Here we have a man who dreamed of political and psychological phenomena drawn directly from real life—a few days after a current political event, the so-called seizure of power. He dreamed about these phenomena so accurately that the dream captured the two forms of alienation so often equated or confused with each other: alienation from the environment and alienation from oneself. And he came to an accurate conclusion: that his attempt in front of everyone to toe the Nazi line, his public humiliation, ended up being nothing but a rite of passage into a new world of totalitarian power—a political maneuver, a cold and cynical human experiment in applying state power to break the individual’s will. The fact that the factory owner crumbled without resistance, but also without his downfall having any purpose or meaning, makes his dream a perfect parable for the creation of the submissive totalitarian subject. By the time he stands there at the end of the dream, unable to lower his arm again now that he’s finally raised it, staring at Goebbels’s clubfoot in petty revenge against the man who holds all the true power and only in that way managing to stay on his own two feet at all, his selfhood has been methodically demolished with the most up-to-date methods, like an old-fashioned house that has to make way for the new order. And yet what has happened to him, while sad, is hardly a tragedy—it even has something of a farce about it. The dream depicts not so much an individual’s fate as a typical event in the process of transformation. He has not even become unheroic, much less an antihero—he has become a nonperson.

***

The factory owner’s dream—what should we call it? “The Dream of the Raised Arm”? “The Dream of Remaking the Individual”?—seemed to have come directly from the same workshop where the totalitarian regime was putting together the mechanisms by which it would function overall. It confirmed an idea I had already had in passing: that dreams like this should be preserved for posterity. They might serve as evidence, if the Nazi regime as a historical phenomenon should ever be brought to trial, for they seemed full of information about people’s emotions, feelings, and motives while they were being turned into cogs of the totalitarian machine. Someone who sits down to keep a diary does so intentionally, and shapes, clarifies, and obscures the material in the process. Dreams of this kind, in contrast—not diaries but nightaries, you might say—emerge from involuntary psychic activity, even as they trace the internal effects of external political events as minutely as a seismograph. Thus dream images might help interpret the structure of a reality about to turn into a nightmare.

And so I began to collect the dreams that the Nazi dictatorship had, as it were, dictated. It was not entirely an easy matter, since more than a few people were nervous about telling me their dreams; I even ran across the dream “It’s forbidden to dream but I’m dreaming anyway” half a dozen times in almost identical form.

I asked the people I came into contact with about their dreams; I didn’t have much access to enthusiastic supporters of the regime, or people benefiting from it, and their internal reactions in this context would in any case not have been particularly useful. I asked the dressmaker, the neighbor, an aunt, a milkman, a friend, almost always without revealing my purpose, since I wanted their answers to be as unembellished as possible. More than once, their lips were unsealed after I told them my factory owner’s dream as an example. Several had been through something similar themselves: dreams about current political events that they had immediately understood and that had made a deep impression on them. Other people were more naive and not entirely clear on the meaning of their dreams. Naturally, each dreamer’s level of understanding and ability to retell their dreams depended on their intelligence and education. Still, whether young lady or old man, manual laborer or professor, however good or bad their memory or expressive ability, all had dreams containing aspects of the relationship between the totalitarian regime and the individual that had not yet been academically formulated, like the elements of “crushing someone’s personhood” in the factory owner’s dream.

It goes without saying that all these dream images were sometimes touched up by the dreamer, consciously or unconsciously. We all know that how a dream is described depends heavily on when it is written down, whether right away or later—dreams written down the same night, as many of my examples were, are of greatest documentary value. When written down later, or retold from memory, conscious ideas play a greater role in the description. But even aside from the fact that it is also interesting to hear how much the waking mind “knew” and supplemented the dream with images from the real environment, these particular dreams about political current events were especially intense, relatively uncomplicated, and less disjointed and erratic than most dreams, since after all they were unambiguously determined. Typically they consisted of a coherent, even dramatic story, and so were easy to remember. And in fact they were remembered—spontaneously, without artificial help—unlike most dreams, especially painful dreams, which are quickly forgotten. (Remembered so well that quite a lot of them were told to me with the same introductory words: “I’ll never forget it.” And after my first publication on this topic, several people told me dreams that lay ten or twenty years in the past by then, dreams that clearly were unforgettable; these retrospective accounts are labeled as such in this book.)

I gathered material in Germany until 1939, when I left the country. Interestingly, the dreams of 1933 and those from later years are remarkably similar. My most revealing examples, however, are from the early, original years of the regime, when it still trod lightly.

***

The most obvious and striking facts of the totalitarian regime—the rules and regulations, laws and ordinances, prescribed and preplanned activities—are the first things to penetrate the dreams of its subjects. The bureaucratic apparatus of offices and officeholders is in fact a dream-protagonist par excellence, macabre and grotesque.

One forty-five-year-old doctor had this dream in 1934, a year into the Third Reich:

At around nine o’clock, after my workday was done and I was about to relax on the sofa with a book on Matthias Grünewald, the walls of my room, of my whole apartment, suddenly disappeared. I looked around in horror and saw that none of the apartments as far as the eye could see had any walls left. I heard a loudspeaker blare: “Per Wall Abolition Decree dated the seventeenth of this month.”

This doctor, deeply troubled by his dream, decided on his own to write it down the next morning (and consequently had further dreams that he was being accused of writing down dreams). He thought further about it and figured out what minor incident of the day before had prompted his dream, which was very revealing—as so often, the personal connection made the historical relevance of the scene depicted in the dream even clearer. In his words:

The block warden had come to me to ask why I hadn’t hung a flag. I reassured him and offered him a glass of liquor, but to myself I thought: “Not on my four walls … not on my four walls.” I have never read a book about Grünewald and don’t own any, but obviously, like many others, I think of his Isenheim Altarpiece as a symbol for Germany at its purest. All the ingredients of the dream and everything I said were political but I am by no means a political person.

“Life Without Walls”—this dream formulation that universalizes in exemplary fashion the plight of an individual who doesn’t want to be part of a collective—could easily be the title of a novel or academic study about life under totalitarianism. And along with capturing perfectly the human condition in a totalitarian world, the doctor’s dream went on to express the only way out of a “life without walls”: the only way to achieve what would later be called inner emigration.

Now that the apartments are totally public, I’m living on the bottom of the sea in order to remain invisible.

An unemployed, liberal, cultured, rather pampered woman of about thirty had a dream in 1933 which, like the doctor’s, revealed the existential nature of the totalitarian world:

The street signs on every corner had been outlawed and posters had been put up in their place, proclaiming in white letters on a black background the twenty words that it was now forbidden to speak. The first word on the list was Lord—in English; I must have dreamed it in English, not German, as a precaution. I forgot the other words, or probably never dreamed them at all, except for the last one, which was: I.

When telling me this dream, she spontaneously added: “In the old days people would have called that a vision.”

It’s true: A vision is an act of seeing, and this radical dictate, whose first commandment was “Thou shalt not speak the name of the Lord” and whose last forbade saying “I,” is an uncannily sharp way of seeing the domain that the twentieth century’s totalitarian regimes have occupied—the empty space between the absence of God and the absence of identity. The basic nature of the dialectic between individual and dictatorship is here revealed while cloaked under a parable. This woman herself admitted with a laugh that her “I” was in general quite prominent. But then we have the details that flesh out the dream: the poster that the dreamer put up like Gessler’s hat; the outlawed, missing street signs symbolizing people’s directionlessness as they are turned into mere cogs. And the simple move of dreaming that the poster listed the English word Lord, which she never uses in her normal life, in place of the German Gott, serves to show that everything high and noble and excellent is forbidden altogether.

This dreamer produced a whole series of such dreams between April and September of 1933—not variations on the same dream, like the factory owner’s, but different ways of processing the same basic theme. While a perfectly normal person in daily life, she proved herself in her dreams to be the equal of Heraclitus’s sibyl, whose “voice reached us across a thousand years”—in a few months of dreams she spanned the Thousand Year Reich of the Nazis, sensing trends, recognizing connections, clarifying obscurities, and vacillating back and forth between easily unmasked realities of everyday life and mysteries lying beneath the visible surface. In short, her dreams distilled the essence of a development which could only lead to public catastrophe and to the loss of her personal world, and expressed it all articulately by moving between tragedy and farce, realism and surrealism. Her dream characters and their actions, their details and nuances, proved to be objectively accurate.

Her second dream, coming not long after the dream of God and Self, dealt with Man and the Devil. Here it is:

I was sitting in a box at the opera, beautifully dressed, my hair done, wearing a new dress. The opera house was huge, with many, many tiers, and I was enjoying many admiring glances. They were performing my favorite opera, The Magic Flute. After the line “That is the Devil, certainly,” a squad of policemen marched in and headed straight toward me, their footsteps ringing out loud and clear. They had discovered by using some kind of machine that I had thought about Hitler when I heard the word Devil. I looked around at all the dressed-up people in the audience, pleading for help with my eyes, but they all just stared straight ahead, mute and expressionless, with not a single face showing even any pity. Actually, the older gentleman in the box next to mine looked kind and elegant, but when I tried to catch his eye he spat at me.

This dreamer understood perfectly the political uses of public humiliation. One guiding theme in this dream, among many other motifs, is the “environment.” The concrete stage-setting of the giant curved tiers of seats in an opera house, filled with fellow men and women who merely stare into space “mute and expressionless” when something happens to someone else, very skillfully depicts this abstract concept, with the extra touch of the man who seems from his appearance to be the last person you’d think would be capable of spitting on this young, vain, well-dressed woman. What she called the faces’ “mute and expressionless” look, the factory owner had called their “emptiness.” (Theodor Haecker, in a dream from 1940, twice mentioned the “impassive faces” of his friends as they just stood and watched him.) Very different people all hit upon the same code for describing a hidden phenomenon of the environment: the atmosphere of total indifference created by environmental pressure and utterly strangling the public sphere.

When asked if she had any idea what the thought-reading machine in her dream was like, the woman answered: “Yes, it was electrical, a maze of wires …” She came up with this symbol of psychological and bodily control, of ever-present possible surveillance, of the infiltration of machines into the course of events, at a time when she could not have known about remote-controlled electronic devices, torture by electric shock, or Orwellian Big Brothers—she had her dream fifteen years before 1984 was even published.

In her third dream, which came after she had been shaken by the reports of book burnings—especially the news she’d heard on the radio, which repeated the words truckloads and bonfires many times—she dreamed:

I knew that all the books were being picked up and burned. But I didn’t want to part with my Don Carlos, the old school copy I’d read so much it had fallen apart. So I hid it under our maid’s bed. But when the storm troopers came to collect the books, they marched right up to the maid’s room, footsteps ringing out loud and clear. [The ringing footsteps and heading straight toward someone were props from her previous dream, and we will encounter them again in many other dreams.] They took the book out from under her bed and threw it onto the back of the truck that was going to the bonfire.

Then I realized that the book I’d hidden wasn’t my old copy of Don Carlos after all, it was an atlas of some kind. Even so, I stood there feeling terribly guilty and let them throw it onto the truck.

She then spontaneously added: “I’d read in a foreign newspaper that during a performance of Don Carlos the crowd had burst into applause at the line ‘O give us freedom of thought.’ Or was that only a dream too?”

The dreamer here extends the characterization, begun in her opera-house dream, of the new kind of individual created by totalitarianism. But here she includes herself in her critique of the environment, recognizing the typical aspects of her own behavior: The book she tries to hide under a bed like a criminal isn’t even a truly forbidden book, only Schiller, and then it turns out she doesn’t even hide that—out of fear and caution she hides an atlas, which is to say, a book with no words at all. And even so, despite being innocent, she feels weighed down with guilt.

While this dream gently suggested that the formula “Keeping Quiet = A Clear Conscience” cannot apply within the new system of moral calculation, her next dream went quite a bit further in that direction. It was a complex dream, with less of a complete plot and harder to understand, but she did understand it.

I dreamed that the milkman, the gas man, the newspaper vendor, the baker, and the plumber were all standing in a circle around me, holding out bills I owed. I was perfectly calm until I saw the chimney sweep in the circle and was startled. (In our family’s secret code, a chimney sweep— Schornsteinfeger—was our name for the SS, because of the two S’s in the word and the black uniforms.) I was in the middle of the circle, like in the children’s game Black Cook, and they were holding out their bills with arms raised in the well-known salute, shouting in chorus: “There’s no question what you’re responsible for.”

The woman knew exactly what lay behind the dream psychologically: On the previous day, her tailor’s son had showed up in full Nazi uniform to collect on a bill for tailoring work she had just had done. Before the national crisis, of course, bills were sent by mail after an appropriate interval. When she asked him what this was all about, he answered, with some embarrassment, that it didn’t mean anything, he just happened to be passing by, and happened by chance to be wearing his uniform. She said, “That’s ridiculous,” but she did pay. A little piece of daily life—but in these times, ordinary everyday incidents were not just ordinary. The woman used this little story to explain in detail how things were operating under the new “block warden system”: the intrusions happening every day and protected by the Party uniform; the many private accounts being settled at the same time; individuals increasingly being encircled by the various little people—Grandpa Tailor, Uncle Shoemaker. All of these figures flitted like phantoms through her Black Cook dream.

The chorus in the dream, though, making her the typical accused person under a totalitarian system with her guilt presumed in advance—“There’s no question about what you’re responsible for”—is also, in German, a clear reference to Goethe’s “All guilt is avenged upon this earth”; it represents her own feelings of guilt at having given in to the pressure despite it being slight pressure, which she called ridiculous and the tailor’s son in uniform called just by chance.

Like the Don Carlos dream before it, this Black Cook dream describes in a very subtle way the first little compromise, the first minor sin of omission, that snowballs until a person’s free will weakens and eventually wastes away altogether. The dream describes normal everyday behavior and the barely perceptible wrongs that people commit, shedding light on a psychological process that even today, despite the best efforts, is extremely hard to explain: the one that makes even those who are technically innocent of crimes guilty.

I would add only that the line about undoubted guilt (“Die Schuld kann nicht bezweifelt werden“) appears in almost identical words in Kafka’s story “In the Penal Colony,” spoken by the officer: “Guilt is never to be doubted” (“Die Schuld ist immer zweifellos“).

This woman’s dreams, full of Orwellian objects and Kafkaesque realizations, tended to repeatedly treat the new circumstances of her environment as static situations: the neighbors with “expressionless faces” sitting around her “in a large circle,” she herself feeling “trapped” or “lost.” Once—in fact on New Year’s Eve, 1933 to 1934, after the customary New Year’s Eve ritual of telling fortunes from the shapes made by dropping molten lead into cold water— she dreamed not even situations but pure impressions, words without any images at all. She wrote the words down that night:

I’m going to hide by covering myself in lead. My tongue is already leaden, locked up in lead. My fear will go away when I’m all lead. I’ll lie there without moving, shot full of lead. When they come for me, I’ll say: Leaden people can’t rise up. Oh no, they’ll try to throw me in the water because I’ve been turned into lead …

Here the dream broke off. We could describe this as a normal anxiety dream—there is no pun in German between the metal lead and the verb to lead or a leader—although it is an unusually poetic one, whose horrors we can feel even without knowing any additional context. (It was used in a short story in 1950.) But the dreamer herself pointed out the scraps of rhyme from the Nazi “Horst-Wessel-Lied” woven into the dream (geschlossen / erschossen [“locked up / shot full”]), and added that she had felt this way, leaden and anxious, for months. If we want to interpret further, we might consider that her phrase “Leaden people can’t rise up” uses the verb aufstehen, the root of Aufstand, “uprising” or “revolution,” so the line has a deeper meaning that she didn’t see despite being so perceptive otherwise.

In any case, her hiding in lead matches the doctor’s hiding at the bottom of the sea as an expression of the wish to withdraw completely from the outside world.

From this handful of fables about a “life without walls,” told in their sleep , it is easy to reconstruct the real circumstances that motivated them. Each of them also represents an abstraction (for instance, the woman’s “environment dreams” exemplify “the destruction of plurality” as well as the feeling of “loneliness in public spaces” that Hannah Arendt would later characterize as the basic quality of totalitarian subjects). These dreams depict not just environmental shocks but the psychological and moral effects of these shocks within the dreamer’s mind.

Adapted from The Third Reich of Dreams: The Nightmares of a Nation, translated by Damion Searls, which will be published by Princeton University Press next month.

Charlotte Beradt (1907–1986) was a Jewish journalist and communist activist based in Berlin during the Third Reich. She fled to New York in 1939 as a refugee, creating a gathering place for other German émigrés, including Hannah Arendt.

Damion Searls is an award-winning translator and writer whose translation of Jon Fosse’s A New Name was short-listed for the International Booker Prize.