Scholars at Harvard in and out of the classroom tell their stories in the Experience series.

Robert Putnam is that rarest of academics: a crossover star.

Putnam, the Peter and Isabel Malkin Professor of Public Policy, Emeritus, grew up in postwar Port Clinton, Ohio, a working-class town on Lake Erie. The kids played Little League together, parents were on the PTA, and everyone in the community gathered in groups to worship, play bridge, and help solve local challenges.

Memories of his youth would become Putnam’s intellectual lodestar for a life of pioneering scholarship and lead to a landmark book, “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community” in 2000, which made him one of the world’s most famous political scientists.

Putnam argued in “Bowling Alone” that the glue that holds communities together comes not from formal institutions, but from social ties forged at places like churches, Elks Club meetings, and bowling leagues. That book, along with his earlier work identifying a now-widely used conflict resolution theory known as “the two-level game,” won him his field’s most prestigious honors. His desire to turn theory into problem-solving policy earned him the ears of Presidents Bill Clinton, George Bush, and Barack Obama.

Putnam, now 83, came to Harvard’s Government Department in 1979. In addition to research and teaching, he held several administrative posts, including dean of Harvard Kennedy School (1989-1991), associate dean of the Faculty of Arts & Sciences, and director of the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. Putnam retired from teaching in 2018 but remains a member of the Kennedy School faculty.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

You’re best known for your work on the important effect that community and social connection have on American society. Tell me about your family life growing up in Port Clinton.

Port Clinton was a small town. I was born in 1941, so I’m a pre-Baby Boomer. I was born in 1941, so I’m a pre-Baby Boomer. My parents were both fairly well-educated. My dad had a master’s degree in business and was the first in his family to go to college. He graduated from the University of Michigan right in the middle of the Depression, so the first 10 years of his career he was looking for jobs.

Then he went into the Navy when the war started, and he lost a leg in the war. Back in the day, military veterans had very little support. He spent a year in the hospital in the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

After the war, he had a wife and a young child — me — and no way to make a living. But my dad was a talented, hard-working guy, and within a couple of years he had started a small construction company from scratch. As a start-up contractor he built houses on spec. He was outgoing and soon became one of the town leaders, very much involved in civic life. But in 1962, while I was in college, there was a big national housing recession, and he went bankrupt.

In short, I grew up in a fairly comfortable life, but that happened to have been the only 10 years of my family’s life when we were comfortable. Shortly after he went bankrupt, he died of a heart attack, so he died very young, leaving me the sole support of my chronically ill mom.

Was your community a “Leave It to Beaver” kind of place—homogenous racially and economically?

No. It was actually very mixed. On the one hand, it was a farming area. I could walk out my back door into farmland. But it was also part of Greater Detroit. There was one big factory in town, Standard Products, which was a supplier to Detroit. They made the little rubber molding around car windows.

Many of the dads of my classmates were UAW workers, so it was solid working class. And then, some kids in my class were kids of farmers, and some were poor. Nobody was very rich and nobody was very poor.

The town was small, and it was very cohesive. We all played on the same basketball teams and Little League. So, growing up in a close family and a close community, I was conscious of the importance of community, even though I wouldn’t have had the words for it.

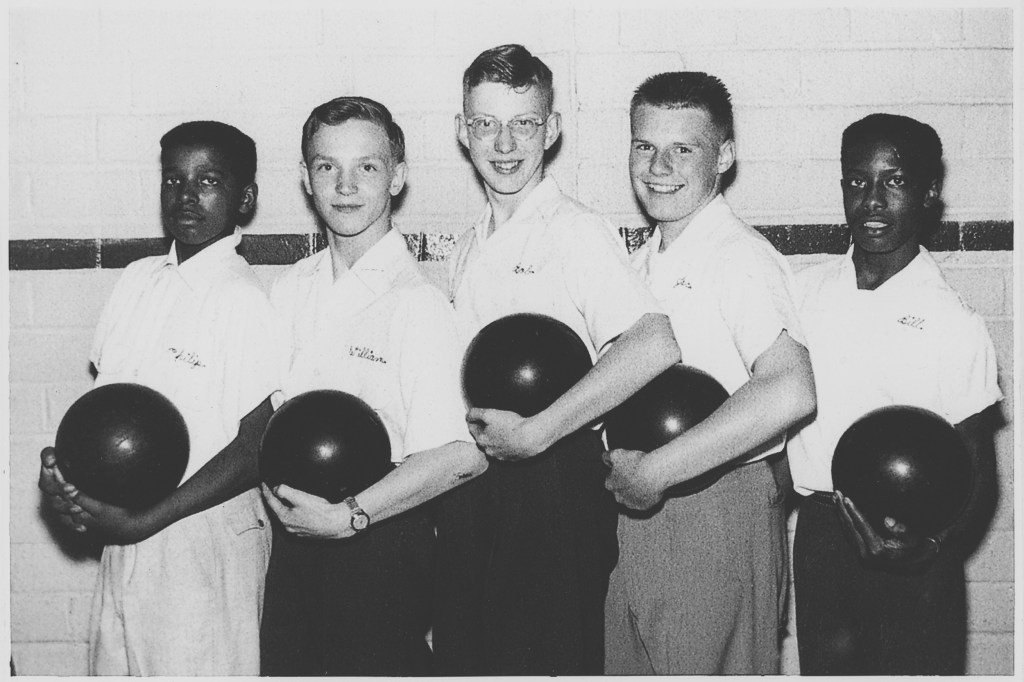

The school was integrated; my bowling team was integrated — three white members and two Black members. The president of the student body was Black, and the second-ranked student in my class was Black. We were all friends.

Were you socially active?

By personality, I’m shy. I was precocious, if I can put it that way. I was focused on books. My mom didn’t want me to be spoiled, so she kept telling me, “You’ve got to get out and join things!”

When I was in grade school, I didn’t play sports. So early every morning, she would get up and play catch with me in front of our house. Ruth Putnam was bound and determined that Bobby Putnam was not going to be an aloof intellectual.

In high school, I belonged to everything. I was in sports; I was in debate; I was in band; I was in the science club; and I was in chorus. I was doing that despite the fact that, inside, I was shy.

Also, I was trying to be one of the guys, so even though I was not a natural athlete at all, in my junior year I went out for football. I had very poor eyesight, so the only position I could play was a position in which you didn’t have to see anything. That meant I was on the offensive line, where all you had to do was try to block the guy in front of you. And I was awful. I was like fifth string or something.

What I didn’t know was that all my classmates were watching the fact that though I was good in school, I had put myself in a position in which I was not good. And, for that reason, they elected me president of the student class. Now, I’m not bragging about that. I’m trying to say, Here’s this little kid. He’s basically shy. His mom is pushing him to get involved in community. He takes on that lesson. And moreover, it turned out the community was a welcoming community not just to me, it was welcoming to everybody.

Putnam (center) with the Port Clinton Ohio Junior High School Bowling Team, c. 1955. “My bowling team was integrated … We were all friends.”

Courtesy of Robert Putnam

You enrolled at Swarthmore College in 1959. What was campus life, especially the political mood, like back then?

Let’s look at Bob Putnam at this moment: He’s a hick from Ohio; he’s a science nerd; he’s a Methodist; and he’s a moderate Republican. In the summer of 1960 — this now sounds crazy — I would write to the Nixon campaign, volunteering.

Swarthmore was small. It was homogeneous socially and intellectually and even politically, and it was intense. And very intellectual. Sophomore year, the fall of 1960, I had to take a distribution course, so I took a course in political science. There were two guys running for president — Kennedy and Nixon.

Swarthmore was very left-wing. It was very socially conscious. Kennedy was a little conservative for many people at Swarthmore.

In this poli-sci class, there was this cute coed named Rosemary sitting in front of me. After class, we started hanging out together. She’s Jewish [Putnam would convert after they married], she comes from a big city — Chicago. Her parents are very clearly New Deal Democrats. We got talking. Of course, we were talking a little bit about politics because that was the class we had just come from.

For our first date, she took me to a Kennedy rally. Sort of, “In your face, Putnam!” And, of course, the next week, I invited her to a Nixon rally. Those were our first two dates. We got along pretty well, and by the election, I was a Democrat.

On Jan. 20, 1961, we said, “What the hell? It’s not that far down to Washington. We’ll go to the inauguration.” We heard Kennedy say with our own ears, “Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country.” I thought he was speaking just to me. And I thought, “I’ve got to do something about America. I have obligations to this country.”

“We heard Kennedy say with our own ears, ‘Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country.’ I thought he was speaking just to me. And I thought, ‘I’ve got to do something about America. I have obligations to this country.’”

Putnam in his Cambridge home.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Not long after, you switched your focus in college to psychology, history, and political science. Who were some of your mentors back then?

In social psychology, I was lucky enough to have two excellent professors. Dean Peabody was one. He was not well known then, but he became a very well-known social psychologist. And Solomon Asch, who at the time was the leading social psychologist in the world. He was a great teacher; he taught small seminars. He was most famous for something called the Asch Social Pressure experiment, which was about the effects of conformity.

Another was Roland Pennock, who was a very distinguished political philosopher. He was known globally, even though he taught at a tiny liberal arts college. I also became quite close to Chuck Gilbert, another Swarthmore professor. The relationships you had with your mentors there were very intense.

After Swarthmore, you studied at Balliol College, Oxford, on a Fulbright scholarship and then headed to Yale for your master’s degree and doctorate. What drew you there?

Yale happened at that point to have the best political science department in the world. They had extremely good political scientists — Bob Lane, Karl Deutsch, and most of all, Bob Dahl, who were the giants of the ’60s and ’70s in political science. We studied in small seminars, so I benefited enormously from working with them.

What was your first big break as a young political scientist, the thing that put you on the professional map?

Professionally the first paper that I wrote as a graduate student was called “Political Attitudes and the Local Community.” It was on this issue of how the community affects the individual. That paper was published in the APSR [American Political Science Review]. That now sometimes happens, but then it was unheard of for a graduate student to publish a paper in the American Political Science Review or World Politics or whatever. It proved to me that I could play in the big leagues in professional terms.

At the time, the Yale paper was just one more term paper. I did not think my whole career was going to be about community. But looking back on it now, I can see, going all the way back to Port Clinton, I was always drawn to these issues. There was something in me that was interested intellectually in the connection between individuals and the community.

Another lucky thing: When I was going on the job market in 1966, ’67, there were very few Ph.D.s coming out then. My birth year was at the end of the baby dearth, during the ’30s and early ’40s, so I had almost no competitors.

But right behind me, universities could see this enormous wave of Boomers entering college. It meant that before I had written a word of my dissertation, I had many tenure-track offers — from Harvard, Yale, Berkeley, UW-Madison, the University of Michigan. This was not because of me; it was because of the times. So, we had all these choices. We could have gone almost anyplace. But Rosemary and I were Midwesterners, and we had parents whom we were close to, so we went to Ann Arbor. That felt like going home.

I’ve always been aware that I am influenced by my environment. So, I choose environments where I’d be led in a certain direction. When I went to Ann Arbor, I knew it was the most quantitative place studying social and political science in the world. I was not that good, but I knew that if I’m there, I would become so — by osmosis. And I did.

“I did not think my whole career was going to be about community. But looking back on it now, I can see, going all the way back to Port Clinton, I was always drawn to these issues.”

After Yale, you joined the Michigan faculty where you taught for several years before taking a detour to work at the White House. You served on the National Security Council under President Jimmy Carter’s legendary national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski. How did that come about?

In about the middle ’70s, I still thought maybe I should be in public service, not just an academic. I got an opportunity to work for a year in the government, and, as it turned out, in the White House. I did that thinking, “Let me put myself there and see whether I like that. Maybe I’ll like it even more than academics or maybe I’ll learn something while I’m there.”

I worked on the staff of the National Security Council for the calendar year 1978. It turned out to be a really important year, and it had a powerful effect on my work in many ways.

It was amazing for me recently to read my own notes from that year, because I could see how much of the whole rest of my career had been affected by that service. I’d never been in government before. I could have taken the Kennedy admonition in that direction. I could have said, “Go into government.” I didn’t. I went into academics.

I took handwritten notes of conversations between the President of the United States Jimmy Carter, and the chancellor of Germany, which, at the time, would have been very highly classified. We were dealing with Iran; we were dealing with nuclear arms control negotiations and U.S.-European relations and U.S.-Soviet relations.

I was just a novice, so I was always working with somebody who knew a lot more than I did. The field I was supposed to be working in was called “global strategy,” but global strategy then actually meant sticking it to the Soviets. So we spent all of our time figuring out — if the Soviets did X, what should be the U.S. response? It was exciting and remarkably interesting.

Did that experience shape any of your subsequent work?

I did some quite significant work based directly on what I learned in Washington. I later invented something called the two-level game model. It turned out to be, in academic terms, a really big deal. The two-level game is what got me into the National Academy of Sciences, not my work on social capital. It came directly out of my service on the NSC.

The other thing that happened was that I was working with Sam Huntington, a famous Harvard professor. He was my boss at the NSC. Somewhat to my surprise, he came away thinking that I was really good. After I finished my time in the NSC, he persuaded Harvard to make me an offer. It seems silly now, but my first thought was, “Why would I want to go to Cambridge? I’m happy. We’re loving it here in Ann Arbor.” But I’ve been at Harvard ever since — nearly half a century.

This idea you’re best known for — that social capital plays a very important role in society — came out of an academic study in Italy that you had worked on for many years. How did that happen?

Most people who know of my work now know only of my work after 1990, when I was already 50 years old. In between the two-level games and “Bowling Alone,” there was this long-term study about Italian regional government. Among academics, it’s at least as well-known as “Bowling Alone.” The book was called “Making Democracy Work.”

If you’re a political scientist and you wanted to study the development of political institutions, logically, you’d like to take the same organization, with the same powers, and the same money and so on, and put it down in different social and economic and political contexts, so you could see which governments flourished and which faltered. That would give you a clue as to how the environment affected the development of these institutions.

Normally, political science is not an experimental study. But while Rosemary and I and our kids were in Italy in 1970, the Italians, without knowing it, created exactly the basis for this kind of study. They created, for the first time, a set of regional governments that had never existed before.

On paper, they were all identical, but in economic and political and cultural and social terms, were vastly different. That unexpectedly turned into a 25-year-long study to measure the success or failure of those new governments.

We had many different hypotheses. We didn’t guess for a long time what turned out to be the critical ingredient — choral societies and football clubs. To what extent did people in a given region join together in things, not just politics, but these informal kinds of connections. We gradually realized, “Whoa! It’s not the education; it’s not the wealth. It’s the choral societies and these informal connections.”

And at the very end of that study, I was a visitor at Oxford and was living in Nuffield College. Late one night, I couldn’t get to sleep. I looked for some book that would put me to sleep. In the library I found this big, thick book of sociological theory called “Foundations of Social Theory” by James Coleman. I thought, “I’ll read this, and I’ll be asleep in 10 minutes.”

I came to this chapter in the book called “Social Capital.” That was the first time I’d ever heard the term, which Coleman used to refer to social connections. Almost immediately, I realized that what I’m talking about in Italy is social capital. It’s these connections, which turn out to be valuable. I ended up not sleeping at all that night. I was so excited.

Up until then, the only people who cared about my work were the half-dozen political scientists in the world who cared about Italian regional government. But now, because I’d introduced the idea of social capital, it got a lot of attention. An Economist review said I was one of the leading social scientists of the last 100 years! That review was another big turning point.

President Barack Obama laughs with Robert Putnam as he awards him the 2012 National Humanities Medal during a ceremony at the White House.

AP File Photo/Carolyn Kaster

As you were finishing that project, you began to see that this idea about social capital might also explain the political, racial, and social divisions that seemed to be underway in the U.S. beginning in the early 1990s?

Yes. We lived in Lexington at that point. I came down to breakfast, and Rosemary showed me a story in The Boston Globe about how the Lexington PTA didn’t have as many members as it used to. And I thought, “Doesn’t everybody always join the PTA?”

I had a research assistant, so we gathered a little data, and it turned out it wasn’t just Lexington, it was everyplace. PTA membership was falling off. I’d grown up in the ’50s, when all parents belonged to the PTA. And I thought, “What’s going on here?” My dad had been in Kiwanis; I wonder if it’s true in Kiwanis? And sure enough, we got the data on Kiwanis membership. It was also declining. That led me pretty soon to say, “I think I’ve stumbled onto something here.”

I had had lunch with a Harvard donor friend of mine, who happened to own a chain of bowling alleys. I said, “It looks to me like people are not bowling in leagues anymore, but they’re still bowling.” He said, “You’ve stumbled onto the major economic problem facing the bowling industry.”

It turns out if you bowl in a league, you drink four times as much beer, and you eat four times as many pretzels. The money in bowling is not in the balls and shoes, it’s in the beer and pretzels.

So his industry was in the strange situation of having more people coming through the door, but revenue was falling because they weren’t drinking as much beer and eating as many pretzels. When I recounted that story to a colleague at the Kennedy School, Jack Donahue, he said “My goodness, you mean they’re bowling alone?”

Soon I delivered a paper at a research conference in Sweden sponsored by the Nobel Foundation. As a joke I titled the draft “Bowling Alone.” It got published in a tiny little journal that had a circulation of about a dozen called the Journal of Democracy. It was published on Jan. 1, 1995, and the same day, the two leading political commentators in America said in their New Year’s columns, “This crazy professor at Harvard has just discovered this amazing effect.”

Within a week, my mailbox, email, and real letters went through the roof. Within about two weeks, I was invited to Camp David to talk with the Clintons. And within about three weeks, Rosemary and I were profiled in People magazine.

Rosemary and Robert Putnam in 1962.

Courtesy of Robert Putnam

Why do you think “Bowling Alone” caught fire so quickly?

I had stumbled onto something that most Americans actually knew privately. I was pretty confident that I was right because thousands of people wrote me saying, “My father was in Rotary, or he was in the Elks. I was proud of him for being in the Elks. I’m not in the Elks. I know I have good reasons, but I kind of feel sorry, and you’ve now helped me understand my personal problem.” For a long time, the academics were skeptical. But underneath, all those thousands of letters suggested to me that I was onto something.

It’s quite unusual for an academic to produce work that’s taken seriously by peers, but also crosses over into the popular culture. What was that like?

I know it’s unusual. There are some advantages and disadvantages to it. I told you about going to the John F. Kennedy inaugural. I wanted to make a difference in America. So, at some level, I welcomed it.

Once the book was published around 2000, I became a kind of celebrity. That gave me a standing to reach to a larger audience and to at least fool myself into thinking that I was actually making a difference. Not change history. The way my team and I talked about it is, we were going to try to bend history. Maybe, at the margins, we could help things a little bit.

You did get some pushback. Some questioned the 1995 paper’s accuracy, and for a while it looked like that might flatten enthusiasm for your findings. What happened?

Early on, I discovered that there had been a methodological mistake in the original article in the Journal of Democracy — not that I had made personally, but I’d used some data from a data archive, and the archive data was wrong. Fortunately, I caught that before anybody else did. But still, if you corrected that mistake, then it was not at all clear that I was right.

At one point, there was a newspaper story saying, “‘Bowling Alone’ is bunk.” That was deeply depressing — clinically. I went through this long depression in which I thought, “Maybe I’m completely wrong.” And then I discovered two data archives, and it turned out I was righter than I’d even suspected I was.

After the publication of this journal article, I got a very generous book deal. I thought I was going to publish it in six months, but I spent the next five years trying to figure out whether it really was true that social capital was declining in America. And if so, why it was true? Did it matter? And what could we do about it? Once the book came out, I did not want to have another “‘Bowling Alone’ is bunk” headline.

I had a big research team by this point. Most social scientists then were doing it like artisans — one person doing all the work. By the time I got to “Bowling Alone,” I was doing industrial social science, if I can put it that way. So, it took me five years, but then it came out, and it was a big hit again. Probably right now, I’m better known than I have been in my whole life even though I’m in my mid-80s. That’s fundamentally because the ensuing years have shown that I was right. I was saved by the data.

In “Join or Die,” a new documentary about your work, there’s an old clip where you lament, “We’re watching ‘Friends’ instead of having friends.” Are you disheartened that the downward trends around community and social connection you identified and warned about in the 1990s have perhaps gotten worse?

Things have gotten worse and when I’ve said that I often leave people with the impression that I think I’ve been a failure. I don’t think I’ve been a failure. Even forgetting about my academic successes, I think I’ve been reasonably successful in raising the alarm about this. But I’ve not found the solution.

Over the last 20, 25 years, most of my time has not been spent on research or writing. It’s been spent on outreach. I have worked with hundreds of grassroots groups all across the country, in every state in America, trying to explain what I’ve found and trying to encourage them to think about what they could do to turn this around. You’d have to ask them to be sure, but I think you would find that they would say, “Putnam has not fixed the problem, and we have not fixed the problem, but he’s put us on the right track.”

The second thing I’ve done is to speak to thousands of journalists and public officials. I’ve tried to make use of the fact that I’ve become something of a celebrity. I could tell you how I spent today, which is in four or five Zoom meetings with somebody from New Hampshire who wants to talk about what they can do here to fix things, and Gov. Josh Shapiro’s team to find out what they could do in Pennsylvania to fix these things, and so on. If I could speak to 500 people a year for 25 years, that’s a lot of people.

“Things have gotten worse and when I’ve said that I often leave people with the impression that I think I’ve been a failure. I don’t think I’ve been a failure. I think I’ve been reasonably successful in raising the alarm about this. But I’ve not found the solution.”

Political scientists aren’t expected to fix the things they study. But you have worked with U.S. presidents and world leaders, policymakers, local officials, and communities to help them address these challenges. Did that come from your desire to live up to President Kennedy’s call to service?

Actually, I do want to fix America! (Laughter.) The irony of all this is: I haven’t quite fixed it, but underneath, that’s been my real motive.

There’s an approach to social science now, which is to say, “We just do the facts. It’s not our business to say what people should do, much less get out and work with them to do it.”

I strongly disagree with that. Of course, there’s a role for people who just do the math. That’s fine. I admire that. Once upon a time, I did it myself. So, I’m not saying political scientists or social scientists shouldn’t do high-tech, quantitative stuff. I’m just saying that, as a group, social scientists should not be focused just on description. They should also be focused on, in some sense, taking a more active role, trying to change. One way or another, ordinary Americans help to fund what is a pretty cushy life for academics like me, and I think we have some obligation to work on problems that concern them.

In the early 2000s, you launched an initiative to convert ideas about social capital into practical solutions, called the Saguaro Seminar. In a recent interview with The New York Times, you called it your biggest failure. Why?

It turned out the problem was too vague. We had this idea — it came from some experts at the Kennedy School — of so-called executive sessions in which you bring together some academics and some practitioners and try to figure out what to do about a problem. And it works for quite specific problems, like crime. We had a report, but the report did not have the impact that we hoped it would have. In retrospect, I think our hopes were exaggerated.

Lots of people have invested a ton of money in having some kind of national commission on one of these big problems — the national commission on polarization or national commission on inequality. None of them have solved the problem. That’s because, I think, fundamentally it’s not an absence of good ideas, it’s an absence of grassroots efforts. Everybody in that group worked hard, and we had some good ideas, but ideas are not enough.

We did make one really good decision. It was made by a guy named Tom Sander, my No. 2 for about 20 years. We were trying to get together a bunch of practitioners from across the nation. We wanted to have a very diverse group. He heard of this young lawyer who was then working as a community organizer in Chicago. And he came back and said, “I think this guy might be our guy.”

Let me guess: His name was Barack Obama?

He was younger than almost anybody else in the group, and he was super smart and very ambitious. Just lovable. We all liked him because he’s very likable and smart. His nickname was “the governor” because we thought, “You’re so good. Maybe someday you might end up being elected governor of Illinois.” Imagine that! (Laughter.) Within five years, he was president of the United States.

While he was president, quite often, he invited me to the White House to speak. In his second term, he awarded me the National Humanities Medal for my work on community. I don’t think I’m exaggerating to say some of his main initiatives came from my talks with him at the White House. And all of that was because Tom Sander, this colleague of mine, had gone looking for a bright young organizer in Chicago.

So, at every stage of my career, I benefited from somebody else. I was lucky in the mentors and colleagues and friends and students that I had. I was lucky that I met my wife. It was not moments in which I was brilliant, it was moments in which I recognized that somebody else had come up with a good idea.

[ad_2]

Source link