In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

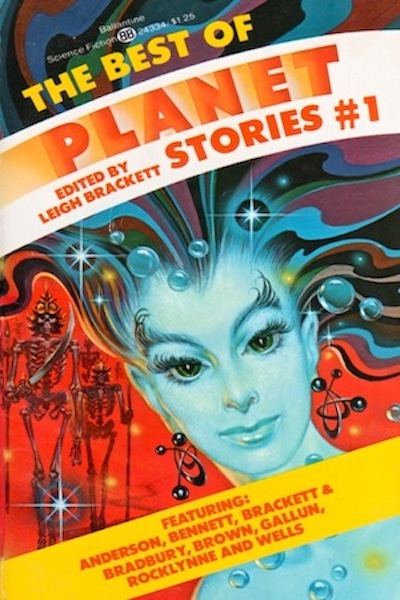

One of the many science fiction magazines that appeared on newsstands in the mid-20th century was Planet Stories, published from 1939 to 1955. It specialized in adventure stories, in the vein of space opera and planetary romance, and was often looked down upon by the more “serious” writers and readers of magazines like Astounding Science Fiction. But in a “Best of” anthology printed by Ballantine Books in 1975 and edited by frequent contributor Leigh Brackett, the author mounts a spirited defense of the magazine, both in her introduction to the volume and in her selection of some excellent stories from its run.

And Brackett didn’t stop there. She took on the idea that adventure stories are somehow less valuable or estimable than stories that focus on the sciences. In her introduction to the volume, she points out that, “The tale of adventure—of great courage and daring, of battle against the forces of darkness and the unknown—has been with the human race since it first learned to talk.” She also showed a bit of disdain for the rigid guidelines Astounding’s editor John Campbell applied to fiction. Her choice of stories shows that there was a wide diversity of tales printed within the pages of Planet Stories. Brackett argues that just because a story is a fun read, that doesn’t prevent it from also having weight and meaning.

I’ve spoken about Planet Stories magazine before in a review of one of Leigh Bracket’s collections, and you can find an Encyclopedia of Science Fiction article on the magazine here. Because the book I’m reviewing today is hard to find, and all the stories it contains (except one) are available to read online at Project Gutenberg, I’ve provided links so you can read the ones that sound interesting.

About the Editor

Leigh Brackett (1915-1978) was a noted science fiction writer and screenwriter, perhaps best-known today for one of her last works, the first draft of the script for Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. I’ve reviewed Brackett’s work before—the omnibus edition Eric John Stark: Outlaw of Mars, the novel The Sword of Rhiannon, the novelette “Lorelei of the Red Mist” in the collection, Three Times Infinity, the short story “Citadel of Lost Ships” in the collection, Swords Against Tomorrow, the collections The Best of Leigh Brackett and The Halfling and Other Stories, the novel The Long Tomorrow, and the Skaith Trilogy: The Ginger Star, The Hounds of Skaith, and The Reavers of Skaith. In each of those columns, you will find more information on Leigh Brackett, her career, and her works. And like many authors whose careers started in the early 20th century, you can find a number of Brackett’s stories and novels on Project Gutenberg.

One and Done

The Best of Planet Stories #1 was unfortunately a “one and done,” the only volume to appear in what had originally been intended as a series. It was published at a time when Leigh Brackett’s science fiction writing career was going through a period of renewal. She had revived her stories of adventurer Eric John Stark, sending him to a new world, Skaith, that orbited a faraway red sun. And she was soon to be tapped to write a script for the sequel to George Lucas’ surprise hit movie, Star Wars. But for some reason, Ballentine’s plans for the anthology series ended with the single volume. It might have been sales figures, it might have been Brackett being busy with other work, or it might have been down to the health issues that would cause her untimely death a few years later. But for whatever reason, this excellent collection stands alone.

As a long-time science fiction fan, I am used to finding works I enjoy that turn out to be “one and done.” It started when I was a kid, and I would have to settle for whatever odd back-issues of used comics were available at the local convenience store, or choose from the limited selection of science fiction books available at the local library, which might only contain one random entry in a series, or maybe just a book that never had a sequel. Sometimes, I would find a sequel and have to imagine what came before it, or find a book with a cliffhanger ending without ever having it resolved. That problem became less common as I got older and gained access to more sources for reading material, but even with additional sources, I wasn’t protected from occasional disappointment.

One of the areas where this kind of disappointment ran rampant was in science fiction on television. In my youth, it seemed that most science fiction shows were doomed to short runs. I loved Time Tunnel, but it ended after a single season. And the same thing happened to Jonny Quest, despite it being the greatest cartoon show in the history of mankind. Star Trek (the original, that is), lasted for three whole seasons, but my boyhood home was out of range of the nearest NBC station. Things did get somewhat better, as there were more TV stations to choose from, and there were shows that ran for multiple seasons, including the many other Star Trek shows, Babylon 5, and a whole host of others. But then a show like Firefly would come along and remind me that disappointment was still an option.

In the end, however, I suppose having a book or show that leaves me wanting more is preferable to one that outstays its welcome.

The Best of Planet Stories #1

The book opens with the long story “Lorelei of the Red Mist” by Leigh Brackett and Ray Bradbury (read it here). The publisher required Brackett to include one of her own tales in each volume of the anthology series, and from a marketing standpoint, it didn’t hurt to include a story whose junior author had become one of the most widely known and acclaimed authors of science fiction in subsequent years. The story is a great example of a planetary romance tale, set among a strange and decadent civilization in a lost corner of Venus that exists under a sea of swirling red mist. The consciousness of an escaping criminal is transferred into a barbarian warrior by a witch who hopes to have him kill her enemies. But the protagonist has his own ideas on how to live, given this second chance at life, and soon is careening from battle to battle.

Leigh Brackett’s work has been a subject of many of my reviews, which are included in the biography above (including a link to a longer review of “Lorelei of the Red Mist”). You can also find my most recent review of Ray Bradbury’s work here, which contains links to my other reviews of his work.

The next story in the collection, “The Star-Mouse,” is by Fredric Brown, a writer who frequently wrote humorous stories, and whose tongue was firmly in his cheek when writing this tale (read it here). It tells the story of a Professor Overburger, who fled a nation that wanted to use his rocket-building skills for evil purposes (and reminds me a bit of Willy Ley). In the best pulp fiction tradition, he is able to build a small but advanced rocket in his home workshop. Wanting to study the effect of rocket travel on living beings, he captures a mouse in his home, planning to use the rodent as a test subject. As a lonely old man, he holds a running one-sided conversation with his tiny friend as he builds the rocket. In his heavily accented English, he names the mouse Mitkey, after a cartoon character.

His rocket works so flawlessly, it achieves escape velocity, and heads out on what the Professor believes will be a one-way journey. But instead, the rocket is captured by tiny aliens who inhabit an asteroid passing near the Earth. The aliens boost Mitkey’s intelligence, and learn about the Earth through examining his memories. Amusingly, because heavily accented English is the only language Mitkey has heard, he speaks the same way, and so do the aliens who learned from him. They send Mitkey home with a machine that can boost the intelligence of other mice, planning for him and his kin to disrupt human civilization. But fortunately for humanity, the best laid plans of mice and men often go awry…

Fredric Brown (1906-1972) was a popular science fiction author, best known for his humorous approach in works like the novel Martians, Go Home. This is the first time I have looked at Brown’s work in this column.

Raymond Z. Gallun’s “Return of a Legend” is an atmospheric tale that follows the adventures of some of the first humans on Mars, who hear the call of the wild, and leave the fledgling Earth colony for life on their own (read it here). This Mars is much harsher than the planet as it was portrayed in many planetary romances, although still more habitable than the world our space probes have revealed. There is life clinging to the planet in all sorts of interesting forms, along with the ruins left by a lost intelligent race. The story is full of compelling adventure, as one person after another leaves the colony to find a way to live on their own terms.

Raymond Z. Gallun (1911-1994) was an American science fiction author who was a prolific contributor to the field, especially in the pre-WWII pulp magazines. This is the first time I have looked at Gallun’s work in this column.

In the “Quest of Thig,” by Basil Wells, alien warriors of the “Horde” capture a human being, and one of them, Thig, is imprinted with his memories and surgically altered to resemble him—a process so convincing that even his wife and children are fooled (read it here). Thig is a scout whose job is to determine whether the Earth is ripe for conquest, and like others of his kind, he’s beem raised without love or affection. But in his months on Earth, he learns that there are other ways to live, and in the end, it is not military might that saves the Earth, but simply the love of a wife and children for their husband and father.

Basil Wells (1912-2003) was an American writer of short stories in science fiction and other genres. This is the first time I have looked at Wells’ work in this column.

Keith Bennett’s “The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears” is one of my favorite science fiction stories of all time, a gritty and realistic tale of survival (read it here). A ship full of “Rocketeers,” members of a new branch of the military, has crashed miles away from their Venus base, and the unit must fight the rest of the way through forbidding jungles full of dangerous plants, animals, and even hostile intelligent inhabitants. Due to scarce resources, the Rocketeers are at risk of being disbanded, and their members incorporated back into the older branches of the military. They are desperate for a success that will prove their worth. And if they can survive, the small band of warriors making their way through the jungle may provide the spark the new service needs.

There is little information on author Keith Bennett on the internet, and this is the first time I have looked at his work in this column. What little information I could find on Bennett was contained in an older Reactor article by David Drake, who cited this story as an early influence on his work, and you can certainly see that influence in Drake’s novel Redliners.

“The Diversifal,” by Ross Rocklynne, is a tale of time travel. Bryan Barrett is told by a man who has traveled back in time that he and a woman he will meet will have a child who becomes the catalyst for the end of humanity. The time traveler constantly meddles with Bryan’s life, and the two grow to hate each other. But with the fate of the world in the balance, how important is one man’s happiness?

I’ve only reviewed Rocklynne’s work once in this column (find it here), and you can find biographical information in that review.

Poul Anderson, always an entertaining writer, gives us “Duel on Syrtis,” a gripping tale of hunter and hunted (read it here). Riordan, a ruthless human big-game hunter who has killed his way across the solar system, wants to hunt a Martian native, or “owlie.” An unscrupulous local agent helps him identify a target, a wily old warrior named Kreega, who in his time was a fierce opponent of human imperialism during the conquest of Mars. Riordan scatters radioactive material to trap Kreega within a five-mile radius of his home, and the hunt begins. The human has a heavy rifle, survival gear, and support from a trained Martian hound and hawk. But this is Kreega’s planet, and his home turf. Soon the roles of hunted and hunter are reversed, and the story ends with a twist worthy of an Edgar Allan Poe tale.

You can find my most recent review of Anderson’s work here, which contains links to my other reviews of his work, and biographical information on the author.

Final Thoughts

The Best of Planet Stories #1 is an excellent collection of tales from the mid-20th century, proof that not all good science fiction of the era was printed in the pages of Astounding. While not every tale in Planet Stories was worthy of note, Brackett makes a good case that, at its best, the magazine could stand equal to the finest of the genre.

I look forward to hearing your thoughts on these tales, and on science fiction adventure stories in general. And I’m curious to hear what science fiction works you’ve been disappointed to find falling into the category of “one and done.”