Dreams + Disillusions | CJ Lim ad Luke Angers | Routledge | $35.99

In an era of shape-shifting Elizabethans, many multiverses, and contested realities, some of them hallucinated by AI, British architect and theorist CJ Lim and his collaborator, Luke Angers, gives us Dreams + Disillusions, a delectable collection of visions of what cities all around the globe might have been, could become, or, if you look at them through this designer’s skewed perspectives, already are. Through a dozen “case studies” and more analytic chapters that romp through everything from the aftermath of London’s great fire to North Korea’s Hermit Kingdom, Lim presents a universe of brightly colored and gravity-defining architectures. While these do not provide recipes for urban improvements, they do offer another way of approaching how to make our cities more sustainable, just, and beautiful.

Like so many architects who wish for a world beyond the dull demands of everyday design drudgery, Lim begins with Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, which for him “present[s] insights on a diversity of urban interpretations and impossible spatial delicacies.” He does not just imagine places faraway in time and place, though. “Cities can be better understood if we trace the dreams and disillusions that form their ideological foundations,” he observed. He goes on to review a wide variety of myths and ideological programs that have shaped cities. Sometimes this influence was deliberate, as in the utopian (or at least idealistic) plans of the 19th and 20th century—expansions such as Cerda’s expansion of Barcelona, the linear cities built by the Soviets, and new cities like Brasília—but often its effects were implicit or hidden.

It is these buried urban myths that interest Lim most. They include the ways in which pilgrimage sites such as Jerusalem have shaped not just their original locations but also other places inspired by these meccas. Lim goes on to find mythic coherence in company towns, campuses, and even detective stories. He thinks that perhaps even the “generic city” Rem Koolhaas posited as the ethos of our modern metropolis can provide a place to find myths whose “mysterious patterns” might inspire us.

It is a shame that Lim does not go further in lifting these magic carpets, however. His chapters are so short and sweeping that barely have we dived into the Moas of Rapa Nui or the possibilities of a post-delirium New York than we are off to another century or continent.

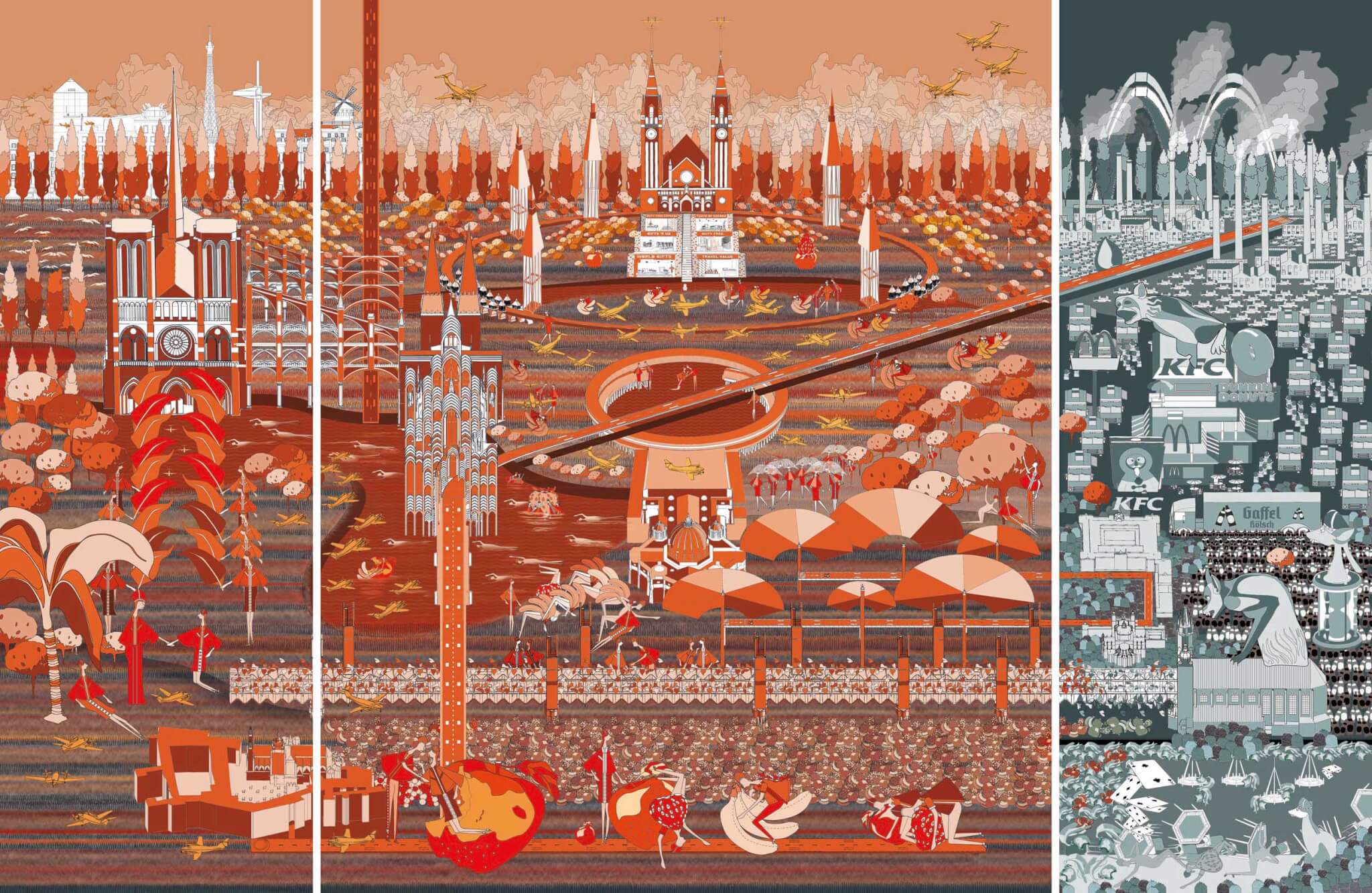

What instead catches our eye are the architect’s case studies. Lim was schooled in the period of imaginative architecture that animated the Architectural Association in London at the end of the last century (think Koolhaas’s and Zaha Hadid’s early visions) and has since developed combinations of digital drawing techniques and cinematic perspectives to produce architecture that is not realized or even realizable. Still, its potentialities are potent. Through imagery he presents alternate histories, such as a London rebuilt after the great fire of 1666 neither according to Christopher Wren’s baroque vision, nor with following pragmatic reality in patterns we have inherited, but with canals copied from Amsterdam that are both sanitary and pleasurable in their effects. He also suggests other futures, such as a Yellow Submarine version of a Manhattan condensed into new, underwater home for the United Nations that highlights and retains the island’s art deco glories while looking forward to a time when most of New York will be submerged.

Lim is never utopian nor dystopian, but instead playfully absurd with just enough realism to make you wonder. In a Case Study 13, titled “Network of Virtuous Mobility,” he reimagines the Vatican as a circular airport that is also a pilgrimage site for global interconnection. Another case study, “The Spun Veil of Pyongyang,” shows “porous skeletal housing units that make anonymity possible” within the bounds of an all-seeing State. Guantanamo Bay, America’s offshore gulag for supposed terrorists becomes, in his most direct critique of current politics, “’Camp America’, an ironic health punishment for the gluttony, greed[,] and sloth of Trump voters.” A more hopeful vision is The Domestication of the Shrew, in which “newly cultivated spaces redefine the suburban ideal by coopting its canonical elements.”

None of this is explained in much detail, nor will you find a single floorplan or section to help you figure out how it all fits together. Buildability is not the point. Instead, the layers of overlapping images and skeletal axonometric outlines of possible structures, often shot through with perspectives ending on soft objects that are somewhere between buildings and furniture, intimate sites that Lim means to embed in your memory and then imagination. They are, he claims, only partial inventions, as they constitute “dreams of alternate pasts and radical futures” that he has found buried in existing cities. They are also memories of revolutionary proposals and destabilizing disasters whose potential has been zapped by the often-uninspired bureaucratic realities of citymaking. Lim works as an archaeologist who finds these sites and then, rather than reconstructing what these alternatives might have “actually” been, imagines what they could be in futures that cannot yet be determined.

This flavor of myth-making enterprise is part of a wider cultural movement. Powered by the possibilities of computer-based technology, but also necessitated by our reexamination of what we thought were the unquestioned facts of our history or even our biological and physical makeup, these myths avoid both the impossibility of perfect utopias and the reductive functionalism of planning. Instead, they propose experimentation in text and image, in the hope that such activity with let us refashion our reality through cultural activities such as art making, storytelling, and architecture. Such an endeavor is a healthy alternative to the contested (and not very productive methods) of traditional economics, planning, or politics, which have made it difficult to find something you might call architecture in the actual mechanics of how our societies build. Lim’s luscious visions may be myths, but they are a welcome tapestry of imagining other worlds, an act of weaving that we need more of now, more than ever.

Aaron Betsky is a critic of architecture, art, and design living in Philadelphia.