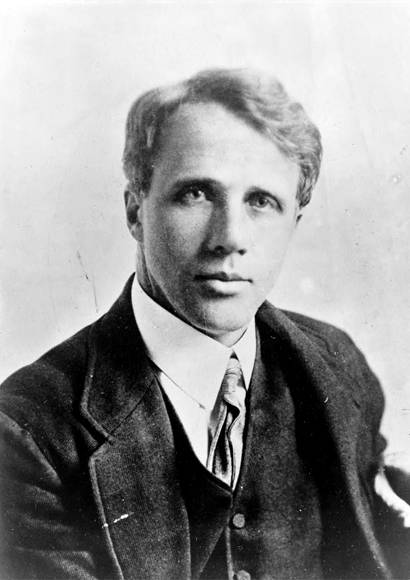

Robert Frost, between 1910 and 1920, via Library of Congress. Public domain.

Though he is most often associated with New England, Robert Frost (1874–1963) was born in San Francisco. He dropped out of both Dartmouth and Harvard, taught school like his mother did before him, and became a farmer, the sleeping-in kind, since he wrote at night. He didn’t publish a book of poems until he was thirty-nine, but went on to win four Pulitzers. By the end of his life, he could fill a stadium for a reading. Frost is still well known, occasionally even beloved, but is significantly more known than he is read. When he is included in a university poetry course, it is often as an example of the conservative poetics from which his more provocative, difficult modernist contemporaries (T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound) sought to depart. A few years ago, I set out to write a dissertation on Frost, hoping that sustained focus on his work might allow me to discover a critical language for talking about accessible poems, the kind anybody could read. My research kept turning up interpretations of Frost’s poems that were smart, even beautiful, but were missing something. It was not until I found the journalist Adam Plunkett’s work that I was able to see what that was. “We misunderstand him,” Plunkett wrote of Frost in a 2014 piece for The New Republic, “when, in studying him, we disregard our unstudied reactions.” We love to point out, for example, that the two roads in “The Road Not Taken” are worn “really about the same,” as though to say that your first impression of the poem—as about choosing the road “less traveled by”—was wrong. For Plunkett, “the wrongness is part of the point, the temptation into believing, as in the speaker’s impression of himself, that you could form yourself by your decisions … as the master of your fate.” Subsequent googling told me that Plunkett had been publishing essays and reviews, mostly about poetry, rather regularly until 2015, when he seemed to have fallen off the edge of the internet. After many search configurations, including “adam plunkett obituary,” I found a brief bio that said he was working on a new critical biography of Robert Frost, the book that would become Love and Need: The Life of Robert Frost’s Poetry, recently published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He responded to my October 2022 email, explaining that he had “stopped writing much journalism as of 2015 so as to avoid distractions from a book project that I thought would take an almost unfathomably long time—two years or perhaps even three. Seven years later, I’m doing my best to polish the third draft.” Just as Plunkett is the unique reader of Frost interested in both our studied and unstudied reactions to the poems, he is the unique biographer of Frost whose work is neither hagiography nor slander. His is a middle way of which, I think, Frost would approve. Recently, we talked on the phone about why Frost has become uncool, Greek drama, and, relatedly, the soul.

INTERVIEWER

What makes you and Frost a good fit?

ADAM PLUNKETT

I tend not to think that stuff other people think is obvious is obvious.

INTERVIEWER

And Frost is obvious?

PLUNKETT

Everyone feels like they have some sense of Frost. Everyone knows a poem or two. That kind of overexposure lends an aspect of at least apparent obviousness. But there’s another aspect, too, which is that many people read Frost for the first time as children and associate him with an early stage of life. There’s a cultural association between the time of exposure and the level of sophistication. You’d sound pretty vulgar if you said, Oh, yeah, I learned to play Bach when I was thirteen—that’s easy stuff. But people really do make pronouncements like that about literature. Someone I met a few years ago, a big poetry person, just could not believe that an adult would spend years of his life thinking about Robert Frost. To her it seemed like doing a Ph.D. in simple algebra.

INTERVIEWER

What is it about his poems that makes people feel that way?

PLUNKETT

They understand the words. People read the poems and think they know what the poems mean. Even when they think that a poem doesn’t mean exactly what it says on the surface, they think they understand the secondary meaning, too. The dark woods in “Stopping by Woods” tend to strike readers as also something other than physical woods, something deeper, which often gets reduced to “death symbolism” but is much richer and subtler than death alone. There’s both a surface coherence and a sense that the thing that’s hinted at beyond the surface is familiar.

INTERVIEWER

Would you say that there’s a direct correlation between Frost’s familiarity and the fact that he’s fallen so out of favor with people who are serious about poetry today?

PLUNKETT

One thing that has been interesting about working on Frost is that so many people come out of the woodwork who turn out to be incredible admirers of him. But he was really far outside of the circle of poets who I was taught when I was in college. This has a lot to do with the fetishization of what’s difficult, especially as both poetry and criticism professionalized. Frost’s difficulties are of a different kind. His genius is harder to see. A lot of his poems tap into something like common culture and common problems, these very basic conflicts that were also the stuff of Greek drama. Those difficulties are different from that of a line break, and they are not the favored difficulties of professional criticism.

INTERVIEWER

How do you think Frost’s difficulty is like that of Greek drama?

PLUNKETT

Take a poem like “Mending Wall.” You have two characters, the speaker and his neighbor, who embody these different ways of ordering space. When they get together, as they do once a year in spring, to mend the stone wall between their properties, the speaker begins to feel that there’s something unnecessary and even untoward about maintaining this boundary. He suggests as much to his neighbor, who just continues to repeat an old folk saying—“Good fences make good neighbors.” If you sit with it, you can see that the poem has the aspect of a Greek drama. It gets down to a conflict, like the one in Antigone, between love and duty, or between obligations to the family versus obligations to the state. You realize that you’re meant to take the speaker’s descriptions, especially of his neighbor, with a bit more than a grain of salt, and that there’s a tremendous amount of balance between these two points of view. It’s an unresolvable problem, how to organize human society. How does a political body at any scale manage borders? Some people may think they have the answer, but I think that if you have any degree of certainty about it, you don’t really understand the problem. I would say the same about reading Frost’s poetry.

INTERVIEWER

That if you think you have the answer, you don’t have it?

PLUNKETT

You don’t quite understand the problem.

INTERVIEWER

You might understand the poem’s language but still not grasp the real-world problem that it describes.

PLUNKETT

Absolutely. Frost’s mind really did work by trying to strip ordinary problems down to the deepest tensions underlying them. That doesn’t mean that he was always wise. He could be a complete bore, and he could be extremely stubborn and crass and prejudiced, especially in his old age. That people tend to rest in easy interpretations of his poems comes in part from the idea that the man who was writing the poetry was in some way simple. But Frost’s simplicity has much more in common with Horace’s phrase “the art that hides art” than with the simplicity of somebody repeating old folk sayings. Yet his sophistication is not the same as that of the intelligentsia. And that’s part of what makes Frost so interesting, that there’s a conflict within him between the life of the mind and a kind of embodied, distributed knowledge that he did not think correlated well with higher education, nor, really, with any of the standard American systems for conferring sophistication. Part of what makes the poetry so good, when it’s good, is that he has a tremendous amount of respect for the sort of person who knows how to mend a wall.

INTERVIEWER

Would you call him a populist?

PLUNKETT

I actually think that it would be a grave mistake to call Frost a populist. Frost was an anti-elitist, not a populist. He even distinguished himself from Carl Sandburg, a genuinely populist contemporary of his, on exactly these grounds—“Carl Sandburg says, ‘The people, yes.’ I say, ‘The people, yes and no.’ ” He also didn’t really think in terms of social class as we understand it. Frost just did not have a sense of himself as in any way superior to people who had less education. In a way that could not be more relevant to the world we’re living in right now, he actually, without condescension or idealization, learned from people who had different backgrounds. He found things to admire in them—different sets of virtues, and certainly different sets of vices than the people who he wound up socializing with once he’d found success. I’d add that, as I see the arc of Frost’s career, the more he’s institutionalized, the worse his writing gets. The more access he has to a privileged, cosmopolitan, educated world, the more that world starts to crowd out his other exposures, and there’s a loss there.

INTERVIEWER

Frost was an important early example of the way a poet could inhabit the university, in roles that many American poets depend on for their livelihood today—he was the original writer in residence, or visiting writer, or professor of the practice, that kind of thing. Yet he was so critical of higher education. How do you think about that tension?

PLUNKETT

Frost had general misgivings about the institutionalization of anything, whether that was an act of imagination that finds its form in the institution of verse, or even a bond of love that finds its form in the institution of marriage. He had a sense of misgiving about what’s lost in learning as it’s institutionalized in college. He occupies this funny role where he has these misgivings but he very much thinks that the institution is better than the utopian alternative. He’s a lapsed Romantic, where both the Romanticism and the lapse are important. He is able to imagine an ideal alternative to the way things are, while being critical of the kind of idealism that would demand that the world actually rise up to meet it.

INTERVIEWER

This makes me think that a better way to describe the tension we’ve been discussing is not between education and the lack thereof but between two different kinds of knowing. Maybe the poems ask you to get your more educated knowing out of the way.

PLUNKETT

You’re certainly right that the work does that—the work at its best, I should say, and that qualification really ought to stand for a lot of it, since it’s not a very large oeuvre of published work and about half of it is really not so good. Though I don’t think that’s a bad ratio for a poet. Poetry is just really, really hard to do well. But when Frost’s work is good, it gives us some capacity to see things stripped away from the judgments we might otherwise bring to them.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a moral dimension to Frost’s work?

PLUNKETT

The relationship between the aesthetic and the moral is quite different for Frost than it is for a lot of secular moderns. He thinks of greatness—though he would never try to formulate it so neatly—partly as being able to see things of value with profound clarity. And seeing things that way was itself a kind of glorification of God for him. His absolute reverence for greatness in art meant that he was hesitant to subordinate his art to ethical demands that most people would probably consider more important. He infuriated his old friend and critical champion Louis Untermeyer, a Jewish American who was doing a great deal to raise awareness of the Holocaust, by refusing to write poetry for the war effort. Frost compared such a demand with that made on ancient Greeks in wartime to appease the gods by destroying beautiful works of art. This perspective can look foreign to a lot of people, especially reading him now. He is also not entirely consistent in holding it.

INTERVIEWER

Frost talks about “coming close to poetry” as a way to describe the experience of connecting with a particular author’s work, but also with the feeling that poetry makes sense as a thing in the world. What would it take for a reader to come close to Frost’s poetry now?

PLUNKETT

Reading Frost requires a kind of modesty and curiosity. Coming to this modesty has been a big part of my own experience with him. At first, I was reading a lot of the poems and thinking, This is dumb. What a dumb way of looking at the world. Then I would think more, and read them again, and the twentieth time, I would realize I had been holding on to a false sense of certainty. Frost called poetry “guessing at myself.” If you have a picture of yourself or of the other or of the world that’s entirely certain, then you can’t really guess at it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think a worldview that is so invested in guessing, or in withholding judgment, comes off as too spiritual for contemporary readers? It can feel so urgent today to come down on a side.

PLUNKETT

There are parts of Frost’s uncertainty that I think can feel profoundly intuitive, even revelatory, these days. The sense of the self as always imperfectly known, always at most guessed at, and the picture that follows of inner life with the constant play of interpretations at the heart of it—what could feel more modern than that? But Frost also had a profound sense of the sacred, and a quite complex sense of the relationship between the sacred and his own often quite profane self. This relationship is hard to get a handle on—in some ways the book is both my effort to wrap my head around it and a history of Frost, and everyone around him, trying to do the same. In a way that was beguiling for everyone, Frost was both a thoroughgoing skeptic about received religious ideas and profoundly religious in the tradition of Anglo-American Puritanism. He was absolutely animated by the conviction that his inner life, his will, was for something far greater than itself. But how much his self had reached the ideals that drove him—this he could only guess at. This kind of inner drama is probably harder to see now for readers less familiar with Protestant habits of feeling.

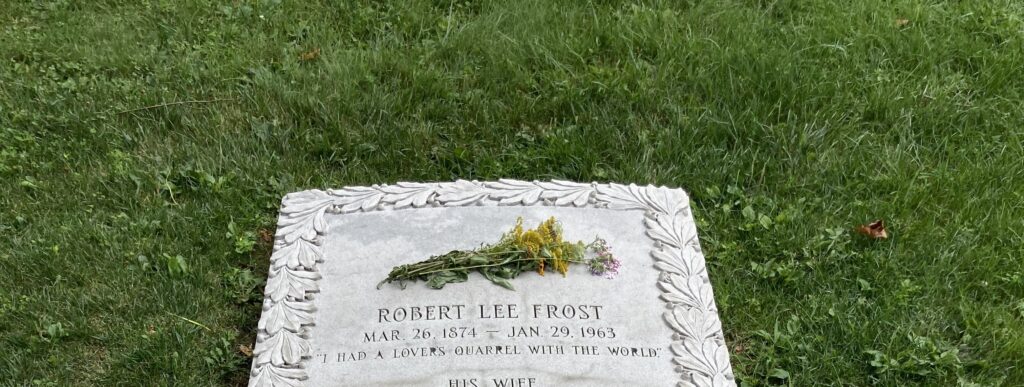

Frost’s gravestone. Photograph courtesy of Jessica Laser.

INTERVIEWER

Are you saying that Frost believed in the soul?

PLUNKETT

Very much, yes.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that Frost is uncool, or has become uncool, because the soul has become uncool? Would a comeback for Frost require a comeback for the soul?

PLUNKETT

The short answer is yes. Uncool is such a great way to put it. All sorts of ways people talk and think about themselves today, even among the most educated, seem animated by a premonition that there’s something more spiritual underlying the world. But it’s still not cool. If you’ve been to college, you’ve probably heard that there’s no rational way to defend that idea. For Frost it comes down to a tension about how much of the world is answerable to reason and how much to some kind of intuition. In a way, his work is all about doubt, but he is a doubter from the vantage of somebody who thinks that there may well be some immortal part of him.

INTERVIEWER

How would you describe Frost’s legacy to someone who has never heard of him?

PLUNKETT

I would say that Frost’s public life in poetry is one of the great ironies of American literary history. An unbelievably strange and idealistic young person, who did not naturally fit into any world in young adulthood, managed by absolute, astonishing drive to study and apprentice his way through obscurity into becoming the very voice of the establishment and the heart of American culture. That’s the history part. As for the poetry part, I’d say that, for me, the biggest gift of the art is his ability to see potentially transcendent beauty and a sense of meaning in things that you’d otherwise think of as too obvious to really regard. It’s a kind of grace of attention. And it’s just really good poetry, you know? It’s great stuff.

INTERVIEWER

Half of it.

PLUNKETT

Half of it. Exactly.

Jessica Laser’s most recent collection of poetry is The Goner School. Her poem “Consecutive Preterite” appeared in issue no. 247.