U.S. productivity soared in the second half of the 20th century, creating benefits for consumers in the form of lower prices across a wide range of goods. But one critical sector proved a glaring exception: housing.

Today the country faces a housing affordability crisis, with ownership out of reach for a growing set of Americans. The price of a new single-family home has more than doubled since 1960, due to a variety of commonly cited factors including labor and material costs. But a recent economics working paper highlights another reason for the rising cost of putting a roof over one’s head: the stifling impact of “not in my backyard,” or NIMBY, land-use policies on builders.

“If there’s one thing we’ve known since the time of Adam Smith, but even more so since the time of Henry Ford, it’s that mass production — repetition — makes things cheap,” said Edward Glaeser, a co-author of the research and the Fred and Eleanor Glimp Professor of Economics. “But land-use regulation stops us from building a mass-produced home and requires instead a very idiosyncratic home. It means every project will be micromanaged. Every project will be small. Every project will be a bespoke build to satisfy five different requirements from the community.”

The new research was inspired by a 2023 paper by University of Chicago economists Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson, who documented what they termed “the strange and awful path” of declining productivity in U.S. construction. The building sector, they found, had outpaced the rest of the U.S. economy throughout the 1950s and well into the ’60s. Then came a dramatic shift. Between 1970 and 2000, even as the overall economy continued to grow, productivity in the construction sector, measured in housing starts per worker, fell by 40 percent.

The findings resonated with Leonardo D’Amico, a Ph.D. economics candidate in the Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences who arrived at Harvard from Italy in 2019. “America is extremely productive in so many industries, especially compared to Europe,” he said. “But housing construction was this glaring example of missing productivity.”

Glaeser and D’Amico partnered with three co-authors, including William R. Kerr, the Dimitri V. D’Arbeloff – MBA Class of 1955 Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, to investigate whether the rise of NIMBYism had driven the sector’s divergence. They started in the early 1900s, seeking a broad view of innovation and productivity among U.S. builders.

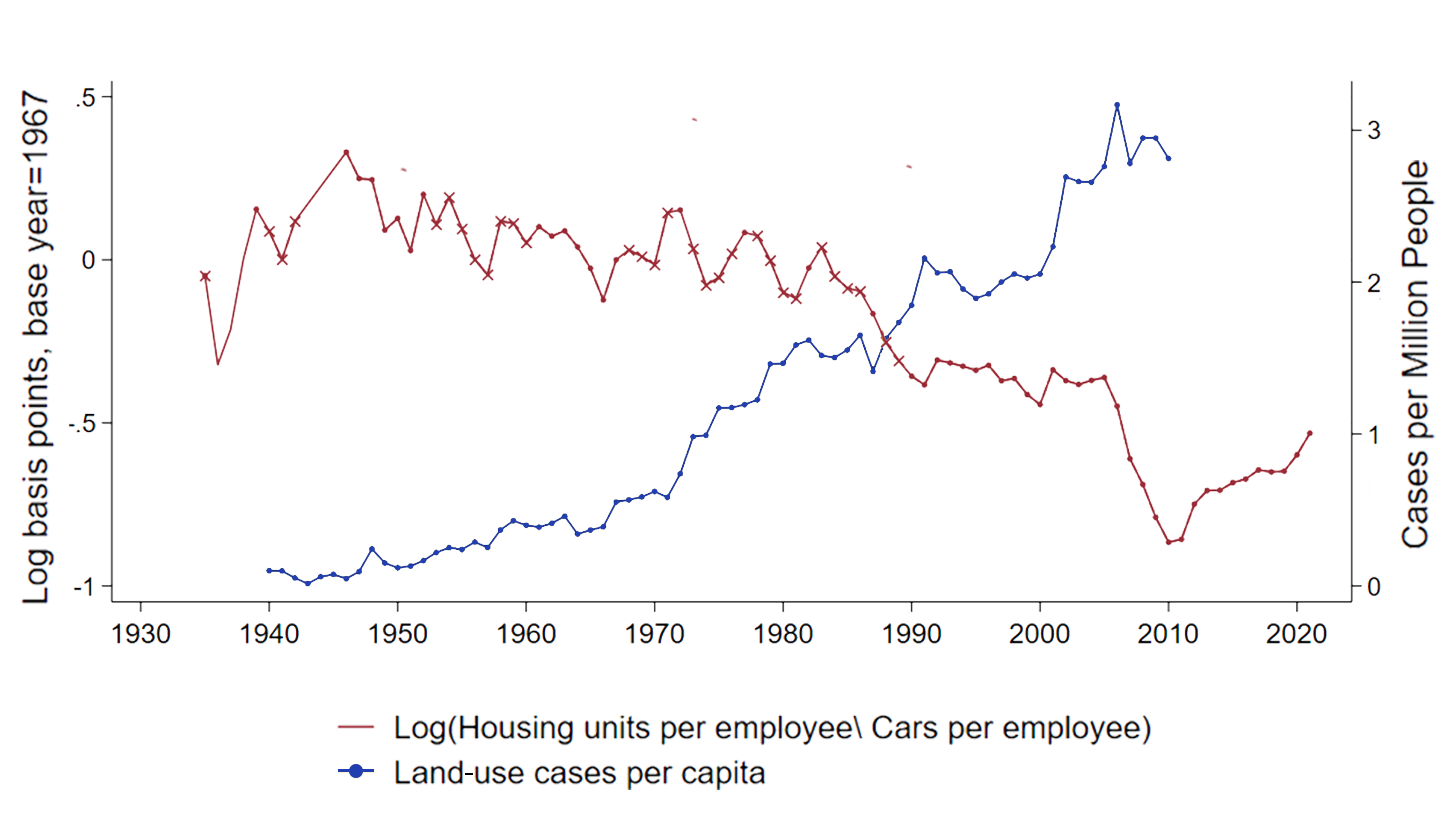

The century of Census data the team collected showed a steep increase in housing productivity from 1935 to 1970. In fact, the researchers saw that the number of homes produced per construction worker during this period often grew faster than total manufacturing output per industrial worker — including the number of cars produced by auto workers. “This goes against the idea that there is something about the housing sector that makes it impossible to grow,” D’Amico emphasized.

Like Goolsbee and Syverson, D’Amico and colleagues found that construction productivity hit reverse circa 1970 — just as the volume of local and regional land-use regulations picked up. In contrast, the authors saw that productivity in auto manufacturing continued to climb, with cars today costing 60 percent less (when adjusted for inflation) than in 1960.

As land-use regulations climbed, housing construction productivity sank compared with auto manufacturing

To explain the role of regulation in high housing costs and falling construction productivity, the new paper presents a model in which the proliferation of land-use regulations served to limit the size of construction projects. Smaller projects, in turn, led to smaller firms with fewer incentives to invest in cost-saving innovations associated with mass production. Testing the model meant quantifying the size of housing developments over time. Drawing on historical real estate data from CoreLogic and other sources, the researchers found that the share of single-family housing yielded by large-scale building projects has indeed been in decline.

“Documenting the size of projects over time is something we’re particularly proud of in terms of empirical contributions,” said Glaeser, an urban economist who has studied housing for more than 25 years. “It enabled us to show the decline or even elimination of really big projects over time.”

The paper includes a section comparing the scale of current projects against that of Long Island’s famous Levittown development, home to more than 17,000 cookie-cutter houses built in the late ’40s and early ’50s.

Edward Glaeser.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Leonardo D’Amico.

Photo courtesy of Leonardo D’Amico

“Entrepreneurs like William Levitt figured out ways to mass-produce housing on America’s suburban frontier,” Glaeser said. “They sent carpenters up and down the street; they sent plumbers up and down the street. It was all moving toward economies of scale, with Levitt moving into modular, prefabricated housing by the 1960s.”

Post-war builders developed thousands of single-family homes on land parcels that averaged more than 5,000 acres. Today, the researchers write, the share of housing built in large projects has fallen by more than one-third, while developments on more than 500 acres are “essentially nonexistent.”

The researchers also detail the productivity advantages enjoyed by large builders like Levitt. Using economic and business Census data, they show that construction firms with 500 or more employees produce four times as many housing units per employee than firms with fewer than 20 employees. Yet employment by large homebuilders started falling in 1973, with no comparable decline in manufacturing or the economy at large.

Firms proved smallest — and least productive — in areas most inclined toward NIMBYism, the researchers found. Homebuilders in these regions navigate rules covering everything from lot size and density to design as well as planning commissions, review boards, and sometimes even voter referendums. But a closer look at the construction sector’s patenting and R&D activity uncovered nationwide impacts.

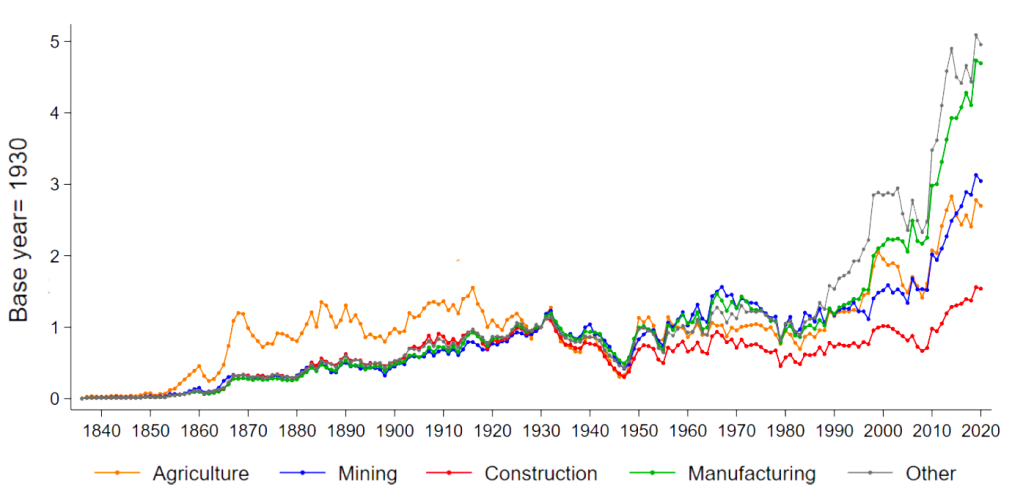

Since the 1970s, construction patents have lagged other industries

“We see in the data that the construction industry was patenting and innovating as much as other industries before the 1970s,” said D’Amico, who is working with fellow Ph.D. candidate Victoria Angelova on a separate paper that investigates the connection between housing costs and fertility rates — underscoring how housing affordability can influence the most fundamental decision-making.

More than 150 years of patenting activity showed the construction industry lagging in the last three decades of the 20th century. “At first we thought maybe it’s because building suppliers were innovating; it’s just not the builders themselves,” D’Amico said. “But we looked at manufacturing firms that serve the construction industry and, remarkably, even their share of innovation has gone down compared to manufacturing firms overall.”

One upshot is what Glaeser characterized as “a massive intergenerational transfer” of housing wealth. He cited his 2017 paper with University of Pennsylvania finance and business economist Joseph Gyourko, who is also a co-author on the new paper. The pair showed that 35- to 44-year-olds in the 50th percentile of U.S. earners averaged nearly $56,000 of housing wealth in 1983, while the same demographic held just $6,000 by 2013. Compare that with median earners ages 65 to 74, who averaged more than $82,000 in 1983 and $100,000 in 2013.

$87,120

Average home equity for 45- to 54-year-olds at the 50th percentile of U.S. earners in 1983

$30,000

Average home equity for 45- to 54-year-olds at the 50th percentile of U.S. earners in 2013

Source: Survey of Consumer Finances

“For me, it harkens back to a model of economic growth and decline that was put forward by Mancur Olson in the 1980s,” said Glaeser, citing the economist/political scientist who described a historical pattern of stable societies generating powerful insiders who guard their own interests by effectively shutting out up-and-comers.

Glaeser was pursuing his Ph.D. at the University of Chicago in the early 1990s when he first encountered Olson’s “The Rise and Decline of Nations” (1982). At the time, the book’s ideas struck him as apt descriptions of the country’s coastal housing markets. But today, Glaeser said, the problem is more widespread.

“Olson captured the unfortunate reality that insiders — or people who have already bought homes — have figured out how to basically stop any new homes from being created anywhere near them,” Glaeser said.

Source link