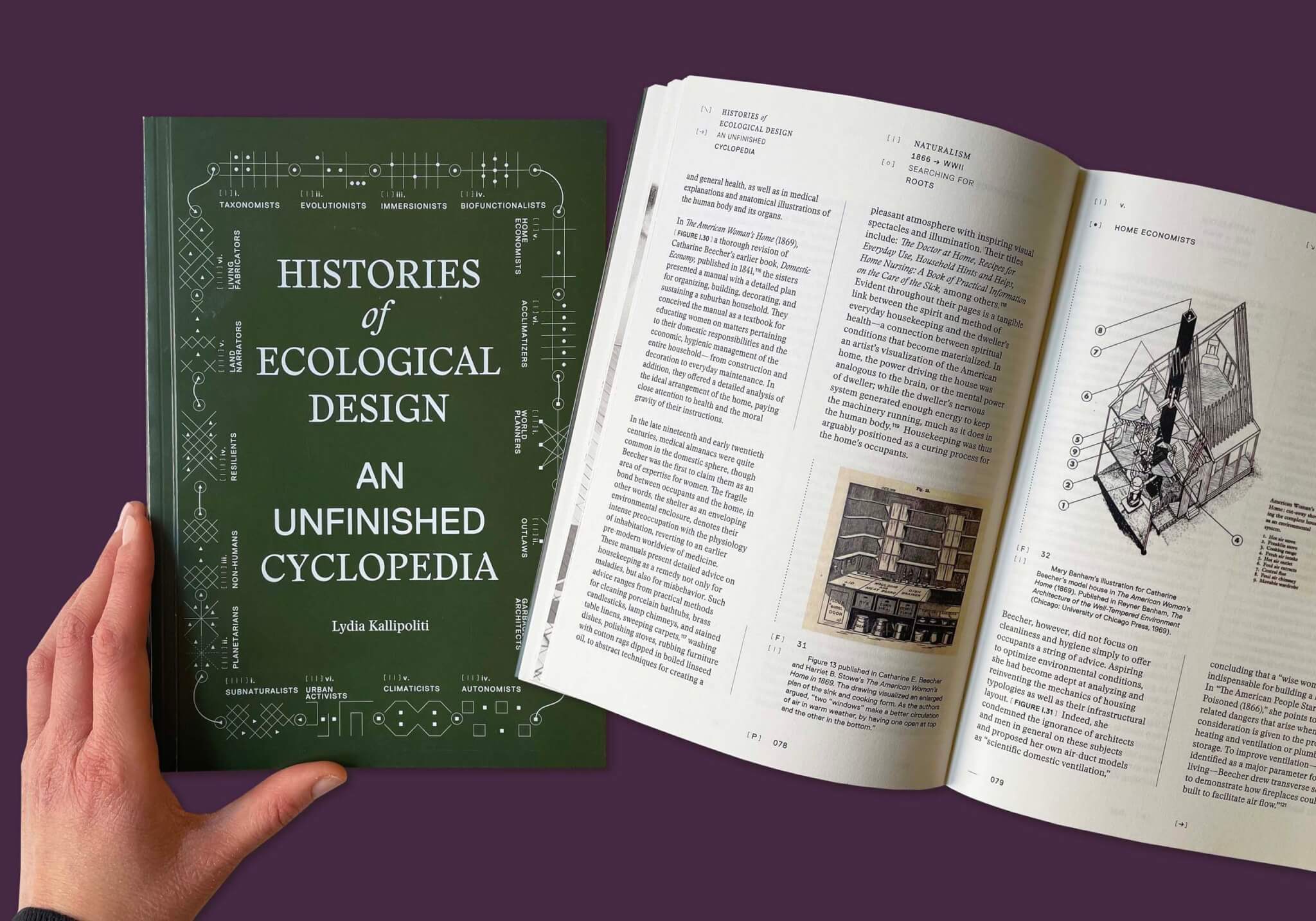

Histories of Ecological Design: An Unfinished Cyclopedia | Lydia Kallipoliti |Actar | $38

It’s happening more and more recently: I scroll through social media and stumble upon a post that brings the urgency of climate change into focus. Depending on the day’s algorithm, it might be a chart of rising global temperatures, a video of a city inundated with flood or famine, or a post from a politician defiantly unmoved by either form of evidence.

My anguish is caused by not only the apparent damage being waged against Earth, our one and only viable source of life, and the untold ripple effects that damage will cause. It is also the fact that, despite every attempt to exploit “nature,” “the environment,” and global “ecology,” institutions still barely understand the concepts these terms attempt to define. These words are recklessly abused by overscaled industries (think of agriculture, construction, and transportation companies espousing “environmentally friendly” or “sustainable” products) to justify endless growth on a planet with finite resources. They engage with a system they do not fully understand and cause irreparable harm that remains stubbornly beyond their grasp.

Rather than succumb to helpless panic in the face of these great unknowns, Lydia Kallipoliti untangles the contemporary relationship between nature and culture in her latest book, Histories of Ecological Design: An Unfinished Cyclopedia. Her ability to place the efforts of “ecological design” within neat little boxes makes a messy history seem orderly. This method is slightly ironic, given her criticism of the rationalistic impulse to categorize, which gave birth to the fateful separation of nature and culture. Her unapologetic creation of hard and fast divisions, however, renders ecological design (a complicated practice, no matter how it is approached) legible to readers who will soon have to determine their position within a rapidly collapsing ecosystem.

Though it claims to be “unfinished” in her subtitle, the book is exhaustive. Everything from romanticism to the Vietnam War, according to Kallipoliti, has informed perceptions of ecology, the never-fully-resolved study of the relations between organisms and their surroundings.

Take her explorations of the home economics movement in the 19th century, for instance. It resulted in a women-led method of seeking connections between the cleanup of the home and the surrounding environment. She then jumps a century to provide a comparable analysis of the widespread disillusionment of the 1960s, which led youths to “drop out” of society and establish novel relationships with each other and their environment. Kallipoliti then arrives at the recent pandemic, in which Zoom meetings “became not only a digital outlet enabled by new media, but also a means of navigating beyond the egosphere of confinement.”

The book’s timeline reveals three distinct eras, labeled Naturalism (1866–WWII), Synthetic Naturalism (WWII–2000), and Dark Naturalism (2000–now). Each has, precisely enough, exactly six types of ecological designers. Kallipoliti’s zoomed-out approach locates the rise of environmentalism more than a century before other contemporary accounts (such as Emerging Ecologies, a MoMA exhibition that closed early this year) and connects them to present-day encounters with the Anthropocene.

Toward the beginning, Kallipoliti provides a diagram that draws lines between ecological designer “types” of different eras. These indicate a genealogy of human responses to the global environment, albeit without much explanation. These actors are most often architects, but there is the occasional artist, scientist, or philosopher filling the more loosely defined role of “designer.”

Sometimes these lines illustrate how prejudices from the 19th century have bled into the 21st (where, for instance, the racially coded practices of “Taxonomists” in the first era, such as Ernst Haeckel and Carolus Linnaeus, gave way to the all-encompassing visions of Buckminster Fuller and John McHale, the “World Planners” of the second era). In other instances, they show how environmental sensitivities have only grown sharper with time (Henry David Thoreau and Frank Lloyd Wright, the “Immersionists” of the first era, became the “Land Narrators” of the present day, such as Francis Kéré or Lesley Lokko).

Perhaps the Cyclopedia’s most valuable contribution as a speculative guidebook is its development of concrete terms for the range of responses to environmental anxiety—everything from corporate geoengineering to Indigenous repatriation—likely felt by anyone who picks up a copy.

“Resilients,” for instance, are defined by their attempt to fight climate change head-on by “ensuring the readiness of cities, renewal of resources, and restoration of ecosystems.” Kallipoliti places large corporate firms, such as Perkins&Will, in this category. The firm developed a proposal for counteracting flooding and sea level rise in Kingston, New York, that additionally serves as a new public space promoting the growth of local biodiversity. This, like other projects put forth by Resilients, implies a future of increasingly large-scale geo-engineering projects designed to counteract our past mistakes as a species. She implies that Resilients are the descendants of “Urban Activists,” though they adopt the historically problematic love of top-down planning and design associated with the World Planners.

By contrast, “Subnaturalists” have broader horizons. Rather than focus on a self-appointed responsibility for saving the world, they interpret the environment instead as a complex territory of relationships that cannot be so easily understood through the scientific method alone. This reorientation, Kallipoliti argues, presents designers “with opportunities to create deviant new natures out of contaminated conditions.” In contrast to the plants and green carpets that often decorate “sustainable” architecture, she describes the work of Spanish architect Andrés Jaque as “architecture [that] can monitor, make visible, explain, and provide a medium through which climate evolution can be sensed.” At MoMA PS1, for instance, Jaque installed a giant water purifier that “made the hitherto hidden urbanism of pipes amongst which we live visible and enjoyable.”

Kallipoliti makes clear that ecological awareness, ultimately, can either lead designers down the path of humility or hubris. Because if the latter “is the ecological society to come,” in the words of philosopher Timothy Morton, “then I really don’t want to live in it.”

Shane Reiner-Roth curates images of the built environment on the Instagram page @everyverything.