I’m sorry I used the word “perfect” when talking about last week’s episodes; that was a mistake, because this one is perfect. There is not a single bad episode of Severance but “Who Is Alive?”, written by Wei-Ning Yu and directed, like so many Severance episodes, by Ben Stiller, might be my favorite. It is hard to top some of the images. I think you know the ones. Also, it opens with the Stone Roses, and I am so curious about why Ms. Cobel has a Stone Roses album, specifically their 1994 album Second Coming. What a title, eh?

But the lyrics are probably more relevant than the title:

Let me put you in the picture

Let me show you what I mean

The messiah is my sister

Ain’t no king, man, she’s my queen

Spoilers for episode three, “Who Is Alive?” below!

It’s hard not to get lost in the details when there are so many good ones, but I have a slightly existential query hanging over my head after this episode, which is: What is time to an innie? What is time if you only experience the same hours of the day over and over again? If you wake up at work, and wake up at work, and wake up at work? When Irv says it’s been a long time since he saw Felicia, she doesn’t correct him, though we know that “five months” number was false and presumably she knows it’s only been a few days. Or does she? When Reghabi asks Mark, as part of the reintegration process, what month it is, he asks if she means what quarter. Of course they know quarters; quarters are the unit of time in which their output is measured. They live in minutes, hours, days, and quarters. Time is a flat circle, or time is a quarterly quota.

The only one concerned with quotas right now is Dylan, who experiences the promised family visit awfully quickly. An effective way to isolate him from the group! He doesn’t want to help in the search for Miss Casey because he is working, diligently, to earn the latest perk: a meeting with a woman (the always great Merritt Wever) who he doesn’t recognize. She is patient and kind and a little bit funny, and there’s a real sort of heartbreak in the questions Dylan asks about his outie self: “He dumb? Is he a dick? What’s wrong with him?” He’s full of judgements that he is only passing on himself, but Gretchen deflects them, neatly, while they sit in the redone security room, once the site of innie Dylan’s triumph Now it is decorated with pictures of him and a woman he doesn’t know. (At least we get a scene with outie Dylan and Gretchen, so we know she’s not just some other random innie told to play this role—which I absolutely thought she was, at first.) It’s an absolute mindfuck. But what isn’t?

If I were to rank the mindfucks in this episode, I would have to put the “inclusively recanonicalized” paintings at the top. Dear Milchick, good job getting promoted, here are some horrifying paintings of your company’s founder in blackface to make you feel seen! As far as misguided corporate attempts to address race go, it’s a whopper. (“Let me put you in the picture,” the Stone Roses croon.)

The paintings are a horror; the extra layer of horror is provided by Natalie, who reports the board’s commentary—“The board is jubilant at your ascendance and wants you to feel appreciated”—with a big smile and wide eyes. You can read a lot of things into that big smile and those wide eyes, depending on where you’re coming from. Every silence in this scene goes on three beats too long, filled with all the things Natalie can’t possibly say when the board is listening. (Lumon is listening!) She was also given these same paintings, which immediately made me wonder what the handbooks say about depicting Keir Eagan with a different skin color (but still with blue eyes!) versus depicting Keir Eagan as a woman.

Natalie says she found the paintings extremely moving, but one can be moved in a lot of ways. (Did they give Felicia these paintings? Does she not have a high enough position yet? Does Felicia have to make these paintings?) “It’s meaningful to see myself reflected in…” Milchick says, and trails off. Is there a way to end that sentence? Eventually, he does the only thing that can be done with such a gift: shoves the paintings in the top of a closet where he doesn’t have to look at them.

It is strange to see Natalie also appear outside of Lumon, smiling broadly at Ricken, who eats up the attention. I would like to commend whoever wrote The You You Are, which is like elevated Deep Thoughts With Jack Handey, but also sometimes skates effectively close to real truths. The fact that it speaks to the innies, who know so little about the you they are, makes perfect sense. The fact that Lumon wants to make an even more innie-palatable version, with “certain verbiage,” is alarming. Don’t forget that Ricken has also written a book about Keir.

Irving has his own side quest this week. As Irv faces the prospect of an Optics & Design empty of Burt, John Turturro shines, making him seem almost fragile, wary of his own feelings, as he drags his heels about going there. But Irv and Felicia talking, eating together, reminiscing about Burt—this is one of the most warm, human, outie-like scenes on the severed floor. And like every moment of real connection, it leads to a small but mighty revelation: To Felicia, the hallway we’ve seen as leading to the Testing Floor is instead the Exports Hall. She’s solemn when she talks about it: “We send a lot of shipments there. Used to go ourselves. But now they send a guy.”

Shipments of what? How many floors are down there?

Ms. Cobel, in her little white Rabbit on the side of a desolate road, might be the most physically, distantly isolated we’ve ever seen a person on this show. The way that opening scene begins—only one truck goes by; there’s no one around, just a silent and dark farmhouse in the background—could just suggest that it’s early morning, or it could, if you’ve been thinking about theories about Severance taking place inside a simulation, suggested a half-done world, a project not yet completed. It becomes difficult, once you start thinking about theories, not to see hints everywhere. “Salt’s Neck” does not seem to be a real place, but neither is Keir, PE. It could be theory fodder, or it could be Cobel on her way to somewhere that means something to her, with her hospital bracelet and a bit of medical tubing along for the ride.

But she bails and returns to Lumon, and has a stilted, fascinating conversation with Helena. Harmony states her demands clearly; Helena replies with Lumon-speak, the practiced corporate mouthpiece. She has a response for every one of Cobel’s claims and requests, until Harmony brings up the fact that Helena is a nepo baby. But even Helena’s response to this—the way she glances down, artfully abashed—feels practiced. There’s a sense of resignation, sure, but absolutely no surprise. What would the board have said to the two of them? (What is the board???) And why does Harmony panic when she sees the tall man waiting by Helena’s car? How much of this season is going to dance around Cobel’s fraught relationship with Lumon, her obsession with her work, her certainty that she’s important, before something becomes clear?

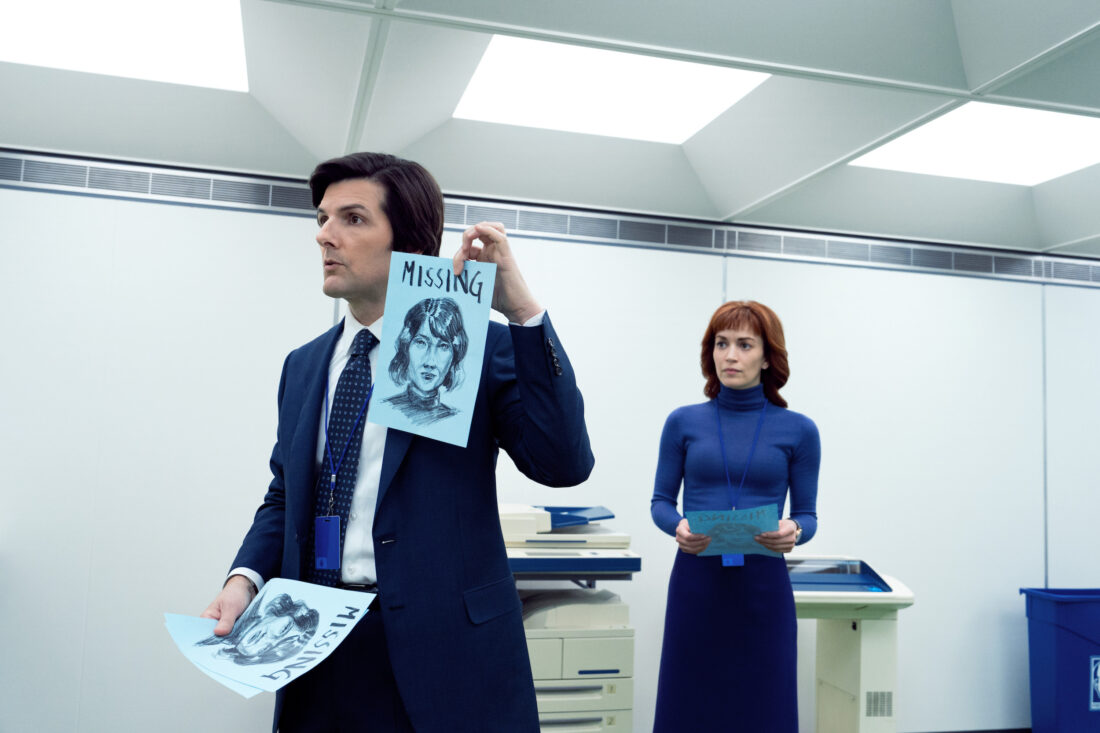

Helena is every inch the Eagan, but Helly has a different sort of day, trailing after Mark while he searches for Miss Casey. I can’t stop thinking about the question of which Helena/Helly is on the severed floor: I don’t think Helena is a good enough actress to pull off pretending to be Helly all the time, but there was something in the way she watched the video of herself kissing Mark, and there’s something off in so many of her interactions here. The look on her face in the hallway scene where Helly and Mark stare at each other. The weird sense that her hair keeps changing colors (and not just from the light). But the way Helena walks to Ms. Cobel and the way Helly walks with Mark—they’re very different walks.

And then there’s the goat room.

To be honest, I did not think I was going to get an answer about the fate of the goats so soon. The goats are fine. (I do wonder where the one man in goat’s clothing got his, uh, outfit.) The goats are under the care of a lightly disheveled Gwendoline Christine, whose character’s name is not mentioned here but is apparently Lorne. “Are you here to kill me?” is a very weird way to say hello, but it tracks with the rumors other departments have been fed about MDR.

I loved, loved, this little bit of folk horror under fluorescent lighting. Lorne’s baffling behavior, the name of the department (Mammalians Nurturable!), the way so many more people rise from the hills, the Being John Malkovich mini-hallway that Mark and Helly crawl down to get there even though there are clearly normal-sized doors—there’s even a snack machine. It is all disconcerting, though also fitting with Keir’s weird pastoral, gazing-over-the-flocks portrait. Are the nurturable mammalians the goats, or the employees? Are these innies learning to nurture?

The Mammalians seem, if possible, even more isolated and weirder than the other severed departments; “We don’t abide such fripperies here” is an old-fashioned turn of phrase, as is everything Lorne says, and these employees have pitchforks rather than computers. They are tight-lipped until Mark and Helly appeal to their sense of innie solidarity—and their concern for their goats. But I think they were protecting Miss Casey. The Mammalians clearly believe the rumors about MDR (Christie’s delivery of “See? Pouchless!” is incredible) and may think the refiners want to find Casey for nefarious reasons.

The goat room sequence is so fascinating that it almost overshadows the real revelation in “Who Is Alive?” which is that Mark opts for reintegration. Outie Mark is in a spy thriller, with the requisite camerawork and speeding (for this show) car. On the outside, he has a plan to send a message to his innie. He got the plan from his computer. Asal Reghabi minces no words when she tells him it won’t work. But he’s trying.

The entire Mark and Asal sequence is an example of how good this series is at giving answers that only raise more questions. Reghabi says, straight out, that Gemma was alive last time she saw her. The camera lingers on Adam Scott’s face for the longest time, letting us process with Mark. Somewhat understandably, he doesn’t question Reghabi, but the obvious question is: When? When was the last time Reghabi saw Gemma? Is she actually trying to help, or does she just want to use Mark to refine her reintegration process? She says she will gather “a version” of Mark that knows his job and his life, but will that version be the man he was before? How did she hear about the overtime contingency, anyway?

Mark doesn’t ask; Mark just says yes, and into the basement they go. A different show, I think, might have left the cliffhanger on Reghabi saying that Gemma was alive. This leaves us on on the cliff of Mark’s personhood: Who will he be, after this procedure? Is he on the table all over again, stuck in a place where he doesn’t know who he is?

Bites From the Snack Machine:

- Felicia wears a gold pinky ring. Does she put it on at the innie/outie locker station? Does she wear it otherwise? Mark changes his watch each morning—and here we see he has a new digital watch—so presumably the innies don’t wear their outies’ accessories. But does this extend to Helly’s earrings? I don’t think Dylan has a wedding ring on. Privileged information.

- Miss Huang did not answer any of Dylan’s questions, including the one about why she’s a kid, but I enjoyed watching him lob at her all the questions I too would like to know the answers to.

- I would like to know why wine is “famously costly.”

- When Mark and Helly are staring at each other in the hall corner, the score, for four notes, does a little tiny riff that’s almost one of the themes from Labyrinth. It’s weird! It was very distracting!

- Of course reintegration begins with Mark wearing a red sweater that looks like the red onesie from the opening credits.

- Did we know Milchick’s first name was Seth?

- Rehgabi tracks five brain waves; refiners are sorting scary numbers into five boxes. Related?