American students’ scores in U.S history and civics keep plummeting, according to the latest Nation’s Report Card, a situation that mirrors the declining levels of civic engagement in the nation. A recent survey found that only 40 percent of American adults could name the three branches of U.S. government and that 22 percent couldn’t identify a single branch.

Martin West, Henry Lee Shattuck Professor of Education, and academic dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, sits on the National Assessment Governing Board, which oversees the Nation’s Report Card. The Gazette interviewed West about the dire state of civic education and the ways to revamp it to help future generations be better citizens. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The results of the latest Nation’s Report Card showed students’ scores declining in U.S. history and civics. How bad were they compared to other subjects and to past scores?

Scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress tests in U.S. history and civics fell substantially in 2022 as compared to the last time they were administered, which was prior to the pandemic in 2018. Those scores, at least as judged by the proficiency levels established by the National Assessment Governing Board, are lower than we see in any other subject.

In 2022, only 14 percent of eighth graders nationwide scored “proficient” in U.S. history, and just 22 percent reached that benchmark in civics. It is also important to acknowledge that, although scores in these subjects fell during the pandemic, they had also been in decline for the decade leading up to the pandemic, and those declines were especially large for low-achieving students. Students’ understanding of U.S. history and civics has been falling and becoming less equal.

What are the reasons for the decline in students’ understanding of U.S. history and civics?

I’m not sure that we know all the reasons why our students are struggling, but a major part of the story is that schools are spending less time on history and civics content than was typical decades ago.

Part of that seems to be a result of school accountability systems that focus primarily, or even exclusively, on student achievement in math and reading, and most states don’t assess students’ performance in other subjects. It’s an exaggeration to say that only what gets tested is what gets taught, but it’s not too far from the truth.

Martin West.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Why should we be concerned about students’ low scores in U.S. history and civics?

One of the core purposes of education, both public and private, is to prepare students for civic life and to be effective citizens in our democracy. When students are unaware of our history and don’t have a solid grasp of our fundamental political institutions, they’re less prepared for civic life.

There’s broad consensus that American democracy is experiencing significant challenges, and it is hard to envision us overcoming those challenges unless citizens understand our political institutions and learn how to engage as participants in our civic life.

It’s also the case that the current moment is not the first time that American democracy has been threatened. An understanding of our nation’s history cannot just equip students for civic life, but hopefully also give them a sense of optimism that we can rise to the challenge.

Compare your score

Four questions taken from the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress eighth-grade tests in civics and history

See how eighth graders performed

What is the main idea of the following quotation?

“So long as we have enough people in this country willing to fight for their rights, we’ll be called a democracy.” — Roger Baldwin, founder of the American Civil Liberties Union

The correct answer: B. In a democracy, citizens should protect their freedoms.

Results for students on this question

| Response category | Percentage |

| A | 6 |

| B | 82 |

| C | 6 |

| D | 5 |

| Omitted | 0 |

What helped farmers in the early Massachusetts Bay Colony be successful?

The correct answer: B. Farming techniques learned from local Native Americans

Results for students on this question

| Response category | Percentage |

| A | 10 |

| B | 47 |

| C | 35 |

| D | 8 |

| Omitted | 0 |

Which of the following is a right guaranteed by the Bill of Rights of the United States Constitution?

The correct answer: C. Right to trial by a jury

Results for students on this question

| Response category | Percentage |

| A | 12 |

| B | 5 |

| C | 45 |

| D | 39 |

| Omitted | 0 |

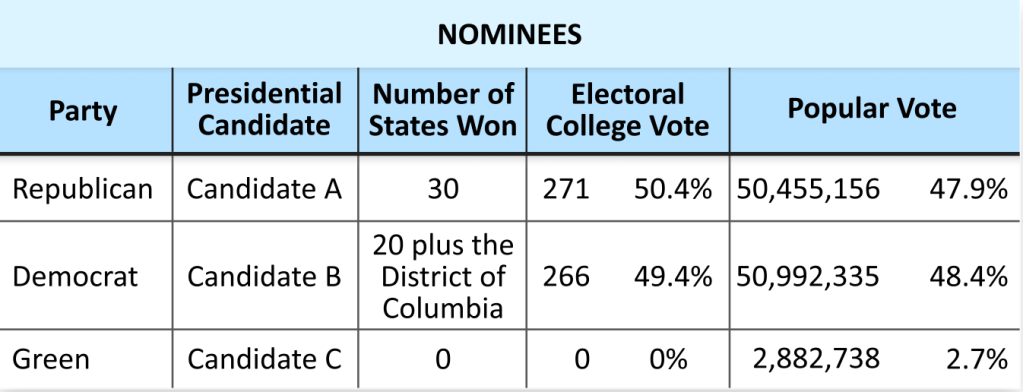

According to the data, which of the following statements about the election is true?

The correct answer: B. Candidate A became president because he won the Electoral College vote.

Results for students on this question

| Response category | Percentage |

| A | 21 |

| B | 45 |

| C | 26 |

| D | 7 |

| Omitted | 1 |

Do you see any link between students’ low proficiency in U.S. history and civics and the level of disaffection among young people with civic life and politics?

We don’t have hard evidence establishing that connection, but in my mind, it’s almost certain that our inattention to civic content in K–12 schools has played a role in young Americans’ cynicism about politics and lack of engagement in the political process.

A 2019 survey found that only 40 percent of American adults could name the three branches of government. Is this something that surprises you?

It’s not a surprise based on the results we see on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. One of the items we administered in 2022, for example, asked students to match each of the three branches of government to its core function. That’s a task that one in six would get right by answering at random, and just one in three students was able to do it correctly.

That same civic deficit that you’re seeing among adults is evident among students even while they are engaging in limited ways with these subjects in school.

Let’s talk about the efforts to revamp civic education in Massachusetts. In 2018, Gov. Charlie Baker signed a law mandating that civic education be taught in eighth grade, not just in high schools. Has the law made any difference or is it too early to tell?

The 2018 law requires that all students take a yearlong civics education course in eighth grade and complete a student-led civics project that year and again in high school.

The implementation of that requirement was obviously disrupted to some extent by the pandemic, but the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education has put a lot of effort into ensuring that districts have access to strong curricular materials as they move forward.

We also hope to roll out a new eighth-grade assessment in civics that is still in a pilot stage.

What grade would you give Massachusetts for the state of civic education?

I would give it a grade of “needs improvement,” but I’m optimistic that things are moving in a positive direction. The law we discussed is still in the process of being implemented.

The history and social science standards we have in Massachusetts are among the best in the nation, and soon we will have an innovative assessment that will allow us to monitor the extent to which students are developing mastery of those standards. Like other states, we have a lot of work to do, but I’m optimistic that we’re headed in the right direction.

What’s challenging about the situation we’re in right now is that we don’t have direct measures of what students know and are able to do. The National Assessment of Educational Progress gives us data for the nation, but unlike in math and reading, we don’t get state-by-state or district-by-district results in history and civics.

That’s why I think it’s very important for states like Massachusetts to develop their own assessments that allow them to track students’ progress and to signal to educators that their efforts in these domains are valued.

Source link